A Divided Aim. Poetry and Propaganda in Oscar Wilde’s «The Ballad of Reading Gaol»

Abstract

Is Oscar Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898) more poetry or rather more propaganda? While writing his famous prison poem, between July and December 1897, mere months after his release from jail, the author himself struggled with what he called ‘a divided aim’ in his ballad about the death by hanging of his former fellow-prisoner Charles Thomas Wooldridge.

This article argues that Wilde’s wrestling with the contending forces of realism versus imagination should be seen in the more general light of how West-European writers over the past two centuries have described the prison experience in imaginative versus autobiographical literature.

Oscar Wilde’s difficulties in overcoming the conflict between reliving and escaping from his traumatic memories are analysed from a biographical and a narratological perspective. This leads to the conclusion that Wilde, reunited with his young lover Lord Alfred Douglas in Napels, succeeded indeed in tying together the divided aims of his creation.

Wilde did so by employing an artful double focus of both identifying with his narrator and with his protagonist. To these two focalisations he was able to add an overarching third voice in the poem that, fully using the potential of the originally Medieval ballad form, unifies the realistic and the romantic forces in The Ballad of Reading Gaol.

«Do all men kill the things they do not love?», the question that the young nobleman Bassanio puts to Shylock in the first scene of the fourth act of The Merchant of Venice, is not one of Shakespeare’s most memorable quotations. If one comes across it, it is almost always in Oscar Wilde’s version, who characteristically turned it around: «Yet each man kills the thing he loves.» It is a returning verse in The Ballad of Reading Gaol and as such it is one of the most famous lines in the poem.

As a matter of fact, Oscar Wilde, born in Dublin in 1854, turned around many more things than just this one Shakespeare-quote: with his spectacular cultural showmanship he stirred the higher social order in London society in the 80’s and 90’s of the nineteenth century. With his witty and paradoxical, but by no means innocent theatre plays and stories, in which adultery, corruption and abuse of power were addressed, he shocked the establishment of his time, just as he turned the hypocritical Victorian morals inside out with his open homosexuality. All this contributed to his tragic downfall in 1895. After two years of imprisonment with hard labour on account of «gross indecencies» (i.e. male homosexual acts) Wilde tried, as a final attempt at a revolution, to reform the English criminal and penal systems.

He did so by writing two long letters to the editor of the Daily Chronicle and by publishing a long poem under the title The Ballad of Reading Gaol. Although this prison ballad, right from the day of its first publication, attracted enormous attention from the press and sold well, and although a stanza from the poem was even quoted during the Parliamentary hearings leading up to the new Prisons Act of 1898, criminal restrictions on the private practicing of male homosexual love in Engeland would only be lifted in 1967. And whether Oscar Wilde’s martyrdom for the cause of penal reform has actually made English prison life fundamentally more humane for those who came after him, is a matter of debate.

In any case, as a person and as a writer Oscar Wilde was involved in various smaller and bigger revolutions: literary, social, theatrical, sexual and criminal. What interests me in particular is to investigate in the following article how this spirit of protest and revolution found its way in The Ballad of Reading Gaol and how it relates to the poetic character of the ballad form. If not his most famous work, The Ballad of Reading Gaol is arguably his most accomplished poem and in any case it was his last completed literary work, begun very shortly after his release from prison in May 1897.

More pointedly, the question is how this poem about the execution by hanging of a condemned prisoner should be read, between what is on the one hand a poetical protest against an inhuman prison system and against capital punishment itself, and on the other a memoir in verse of the author’s own misery during his two years’ solitary confinement. Some have criticised the poem for being too much of a pamphlet (e.g. BECKSON 1970: 214), others for it being – like the rest of Wilde’s poetic work – too artificial (e.g. YEATS 1936: vii).

Wilde himself wrestled explicitly with the competing realistic and romantic forces in the poem. During the process of creation he wrote (on 8th October 1897) to his friend and designated exécuteur-littéraire Robert Ross: «The poem suffers under the difficulty of a divided aim in style. Some is realistic, some is romantic: some poetry, some propaganda» (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 956). In his detailed analysis of Wilde’s final years Frankel even calls it «a hybrid production» (FRANKEL 2017: 182). But is that really what it is? Does the finished poem indeed so blatantly show the author’s internal conflict? And if that conflict did give the author such problems, then what kind of problems were these, how did they manifest themselves and how did Wilde try to handle them, or even solve them?

Before being able to say something about the poetic genesis of The Ballad of Reading Gaol, we have to look at the origins of the poem. That means we first have to go back to that fateful Sunday, 29th March 1896, to the village of Clewer, near Windsor, not far from London, in the County of Berkshire.

A death foretold

By all accounts Laura Ellen Glendell, affectionately called ‘Nell’ by her family and friends, was a bit of a flirt, and her husband, Charles Thomas Wooldridge, was said to be quick-tempered. All that is difficult to check, but various witnesses have declared that they sometimes heard the young couple quarrel for hours on end. Wooldridge was a soldier in an illustrious Cavalry regiment, the Royal Horse Guards, also known as ‘the Blues’ for the colour of their tunic. The couple had married quietly in 1894, without the required formal permission from Charles’s commanding officer, and had settled at nr. 21 Alma Terrace in Clewer. Nell was probably 22 years old at the time, her husband was 29.

While Wooldridge was mostly taken up by his duties in the nearby barracks in Windsor, Nell worked as an assistant in the local post office. A teenage girl by the name of Alice Cox, supposedly a niece of her husband’s, came to live in their house to work as a domestic servant. When Wooldridge’s regiment was transferred to barracks in Regent’s Park, the couple had to live apart, which put an additional strain on their relationship. After awhile, Charles heard that his wife was using her maiden name again, and rumour had it that she was seeing another soldier, one Robert Harvey. First, Wooldridge ordered his wife to come to his barracks to discuss her way of life, and when she didn’t show up, Wooldridge went to Clewer in a rage. Their quarrel quickly turned into a fight, which left Nell with two black eyes and a injured nose. From then on she refused to have anything to do with her husband and she drafted a declaration for him to sign that he would leave her alone. She even wrote to his commanding officer urging him to make her husband sign the document.

On 29th March at 9.00 an angry Wooldridge was at the door of 21 Alma Terrace again. To avoid a scene in front of the house he was let in by Alice Cox. That turned out to be a mistake, as Nell was absolutely unwilling to receive him. She promptly decided to leave the house and stood for a moment in the doorway waiting for her coat and hat, when Wooldridge produced a razor blade, with which he slashed her throat three times. As reports in the Reading Mercury would later have it, he did so «in a very determined manner» (MASON 1914: 426). Wooldridge then walked out of the house and gave himself up to the first policeman he encountered in the street, police constable Foster.

The trial of Charles Thomas Wooldridge was a predictable one. The jury was out no more than two minutes and pronounced him guilty of murder, so that the Judge, Sir Henry Hawkins, had no alternative but to sentence the soldier to death by hanging. The fact of his having brought the cut-throat razor pointed to the premeditated character of his crime, which rendered a more lenient sentence impossible. Several petitions were drafted, in order for Wooldridge to be spared the death penalty, but to no avail. Wooldridge himself declared that, however he regretted his deed, he was ready to receive his due punishment, and so he did.

On 7 July, 1896 at 7.45 am the bell of the 12th century St. Lawrence’s Church on Town Hall Square in Reading, about 20 kilometers west of Windsor in the same County of Berkshire, began to toll. This was the traditional sign that a hanging was imminent in the nearby prison, where Charles Thomas Wooldridge had been held on remand in anticipation of the outcome of his trial.

Executions such as this one were not a daily occurence in Reading Prison. The previous one had taken place 2,5 years ago, so the general excitement in the building, especially among the inmates, was considerable (STOKES 2007: 186). The scaffold on which Wooldridge was to die, had been duly erected in a shed with a glass roof on the prison’s exercise yard, which in the past had been used as a photographer’s studio. There, what is nowadays called a ‘mug shot’ was made of every incoming prisoner.1

By all accounts Wooldridge had behaved in a calm and exemplary way, during the nearly three months of his confinement. Similarly, he now conducted himself without any outward signs of excitement in the small procession from his cell to the shed. Apart from Wooldridge the procession consisted of the prison governor (Major J.O. Nelson), the prison chaplain (the Rev. Martin Thomas Friend), the prison doctor (Dr. Oliver Maurice), a policeman, two guards and the hangman, James Billington (MONTGOMERY HYDE 1963: 65-69). The latter’s gruesome task, however, was not in any way alleviated by the orderliness of the procession. Billington was an experienced hangman, who had fulfilled the official function of ‘Chief Executioner of Great Britain and Ireland’ since 1891. Looking at the prisoner’s rather long neck he correctly gave him a somewhat longer drop than usual. No wonder that on the official death certificate the cause of Wooldridge’s death was given as «dislocation of the vertebrae». His neck was stretched nearly 30 centimeters by the hanging (STOKES 2007: 186). Charles Thomas Wooldridge died shortly after 8.00 in the morning of 7th July 1896 in Her Majesty’s Prison in Reading, Berkshire.

Prisoners

The death by hanging of trooper Wooldridge would not have received more attention than a mere listing in the criminal records of the county of Berkshire and due notices in the local press of the day, were it not for the fact that among the 150 or so other inmates of Reading prison there was a writer for whom Charles Wooldridge’s tragic fate was something to which he responded with all his powers of empathy and even identification. The writer in question was Oscar Wilde and it was this incident during his two years in prison ‘that affected him most’ (STURGIS 2018: 608). As we will see, his response went far beyond the general feeling of curiosity and sensation that must have reverberated for weeks among the prisoners, both before and after the events of 7th July.

Oscar Wilde, 41 years old at the time, was held in solitary confinement since 25th May 1895, the day he had been convicted to two years’ imprisonment with hard labour. Having first been held consecutively in Newgate, Holloway, Pentonville and Wandsworth prisons, he had been in Reading since 20th November 1895, so at the time of Wooldridge’s execution over half a year. Wilde’s prosecution and conviction had been in complete accordance with his country’s laws of the time, and the worst of all was that it was he himself who had set his prosecution in motion, by instituting a foolish libel suit against the father of his much younger lover, Lord Alfred Douglas. This father, who loathed the openly homosexual lifestyle of his youngest son and the 16-years older Wilde, had accused Wilde in private and finally also in public of «posing as» a sodomite.

Instead of ignoring this accusation, which was in fact an understatement, and continuing his brilliant literary, dramatic and journalistic career, Wilde chose to challenge John Sholto Douglas, ninth Marquess of Queensberry, before the courts. Douglas père turned out to be a formidable opponant, who used every possible means to destroy Wilde. In particular, Queensberry’s lawyers and detectives unearthed – whether or not by bribing – so much incriminating evidence from young male prostitutes and hotel employees, that Wilde was soon forced to surrender to the plea of justification and to drop his libel suit, Not only was he left with the substantial legal costs of the case, but in light of Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, which prohibited male sexual acts even in private, the public presecutor could not possibly overlook the evidence that had been produced in this civil law suit. In a spirit of recklessness and defiance Wilde refused to flee the country, and stayed «to face the music». On 5th April 1895 at 6.10 pm he was arrested in his room at the Cadogan Hotel on Dover Street.

After two criminal trials and his conviction on 25th May Oscar Wilde was led out of the central criminal court in the Old Bailey, with two years of solitary confinement before him. The «hard labour» to which he was also convicted turned out to consist mainly of sewing mail bags or the so-called «oakum picking». All these lessons in humility were made the more difficult to learn by bad food, uniform prison clothing, a plank bed in a small cell with sanitary facilities on the level of a pigsty.

All these deprivations were even harder to suffer for someone who for ten years had celebrated great successes in London as a writer, a critic, an aesthete, a cultural phenomenon, someone who was accustomed to a refined and extravagant style of living, with first nights, midnight soupers, champagne and inscribed silver cigarette cases as special souvenirs of special meetings. Since his spectacular tour through the United States and Canada in 1882 – with more than 140 public lectures – Wilde was completely used to having his own way in life and to enjoy that life as much as possible. His marriage in 1884 and the two children that were born from it, had not substantially influenced this hedonistic view of life.

C.T.W.

When Charles Thomas Wooldridge in early April 1896 was brought into Reading prison, Oscar Wilde was approximately half-way through his two years’ prison term. He had lost a lot of weight, suffered from both insomnia and diarrhoea, loathed the daily prison fodder and had developed a middle ear infection, probably as a result of an earlier fall on his head in Wandsworth prison. Meanwhile, his books, paintings and furniture had been auctioned off in an unsuccessful attempt to satisfy his creditors, so that he had also been declared bankrupt.

Although Reading was an improvement on the much larger London City prisons where he had been previously held, the authoritarian and according to Wilde even sadistic governor of Reading prison, Lieutenant-Colonel Henry B. Isaacson, was responsible for much unnecessary suffering and misery. It was only after Isaacson was replaced in July 1896 by the more humane Major J.O. Nelson that Wilde’s condition slowly improved, especially after being given more books to read, and even pen, paper and ink to write.

The latter materials he used not only for correspondence, but especially for writing the long letter to Lord Alfred Douglas, that from its first posthumous publication in book form in 1905 would be known as De Profundis. After his release on 19th May 1897 Wilde would immediately set himself to write the first of two letters to the Editor of the Daily Chronicle, strongly protesting against the unnecessary cruelty of English prison life, even in the case of small children.

In particular, Wilde protested against the treatment of a prisoner named James Edward Prince, with prison number A.2.11 (meaning that he was in cell nr. 11 on the second floor of the A-wing), who by way of disciplinary measure had received repeated flogging although clearly, rather than disobeying the little rules of daily prison life, he was mentally ill and at breaking point. Another fellow-inmate with whom Wilde was in direct touch was the nameless C.4.8, who once remarked to the writer that for the likes of him prison life would probably be harder than for the others (ELLMANN 1987: 466).

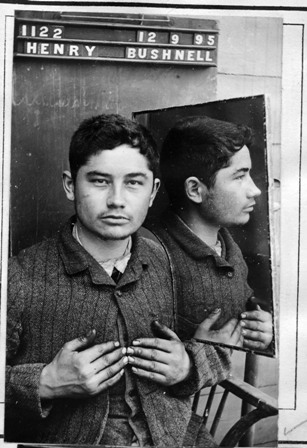

After his release from prison Oscar Wilde sent various sums of money to a dozen of his old fellow-inmates, for example to Henry Bushnell, who was repeatedly held in Reading for stealing plants, nuts and a coat (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 860, STONELEY 2014: 461). Wilde could ill afford such generosity, but he felt that these were debts of honour. It is no exaggeration to say that the greatest debt of honour for Oscar Wilde was his memory of Charles Thomas Wooldridge, if only because it was a debt that could never be repaid in money.

It is unlikely that Wilde and Wooldridge ever spoke to each other, but still the soldier’s tragic fate had a great symbolic significance for the writer, as a counterpoint, even a focal point for his own miserable memories of his prison years. The earliest written trace of Wilde’s intention – apart from De Profundis and the two letters to the Daily Chronicle – to make use of his prison experience in the form of new literary work, is a letter from April 1897 smuggled to the prison warder Tom Martin, in which Wilde writes: «I hope to write about prison life and to try and change it for others, but it is too terrible and ugly to make a work of art of» (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 798). In the manuscript of De Profundis, completed in March of that same year, he would write, similarly: «The prison-system is absolutely and entirely wrong. I would give anything to be able to alter it when I go out. I entend to try» (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 754). That it is indeed very difficult to reconcile the terrible ugliness of prison life with the artful form of a literary work, Wilde would soon find out.

The day after his release, 20th May 1897, he left England once and for all, taking the night boat to Dieppe, on the French coast of Normandy. Staying the first few weeks in a hotel, from mid-June onwards he rented a house, the Chalet Bourgeat, a few kilometers to the North in Berneval-sur-Mer. Writing from the Café Suisse in Dieppe, he announces on 7th July 1897 to the love of his life, Lord Alfred Douglas in Paris: «Tomorrow, I am going to write my poem» (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 910).2 It seems highly unlikely that the date of this solemn announcement would be purely accidental, it being the exact first anniversary of the execution of the ‘trooper of the Royal Horse Guards’ who would become famous as the «C.T.W.» to whom Oscar Wilde dedicated his Ballad of Reading Gaol.

Sources of inspiration

The Ballad of Reading Gaol is written in a traditional, originally medieval poetic form. The specific character of the ballad resides in the formal division in regular stanzas, in the rhyme scheme that often contains both end rhyme and internal rhyme, the brief lines with their songlike metre and the general tone and atmosphere suggesting and facilitating oral recitation. Wilde’s ballad has a total of 109 stanzas, alternating within each stanza from four to three metrical feet, and rhyming according to the scheme a-b-c-b-d-b. The poem is divided into six sections of uneven length.

Many famous ballads in the history of English literature have been suggested as possible sources of inspiration for Oscar Wilde, like The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798) by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, La Belle Dame Sans Merci (1819) by John Keats, Thomas Hood’s The Dream of Eugene Aram (1831), A Shropshire Lad (1887) by A.E. Housman and Rudyard Kipling’s Danny Deever (1890). There is something to be said for each of these comparisons. Coleridge’s poem is about doom, Keats tells a story love and death, Hood’s protagonist is a murderer, Housman writes about a soldier and a prison and in Kipling’s work a British soldier is even executed for murder. At the same time, the differences in the formal details, in length and in versification are such, that one may ask whether the suggested parallels are not inherent in the tradition of the ballad, a poetic form that since the Middle Ages has always been the ideal vehicle for telling tragic stories of soldiers, wanderers, doomed lives and loves, murder, revenge and punishment. Foreign examples like François Villon’s Ballade des pendus and Goethe’s Erlkönig show that this formal and thematic character of the ballad is certainly not restricted to English literature.

Instead of randomly pointing to famous ballads that may have inspired the author, it is more relevant to look at what books Oscar Wilde had been reading recently, in the last period of his imprisonment in Reading. In particular, in December 1896, thanks to various friends and under the more benign regime of the new prison-governor, Wilde received a copy of all three volumes of Reliques of Ancient English Poetry. Published originally in 1765 this collection of 180 ballads was assembled by the Irish bishop Thomas Percy. The collection not only achieved huge popularity among readers, but also strongly influenced the early English Romantic writers, like Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Walter Scott and William Wordsworth and thus helped to raise this popular form to the level of literary expression (BRISTOW, MITCHELL 2015: 112).

Let us look for a moment at the following opening stanza of one of Percy’s ballads, entitled The Patient Countess:

Impatience changes smoke to flame,

And jealousy is hell;

Some wives by patience have reduc’d

Ill husbands to live well:

As did the lady of an earl,

Of whom I now shall tell.3

We immediately recognize the form, the rhyme scheme and the metre of Wilde’s ballad. The same goes for an originally 17th century ballad like Ulysses and the Syren, the Scottish ballads Gilderoy and Robin and Makyne and the well-known prison poem To Althea, From Prison by Richard Lovelace, all included in Bisshop Percy’s anthology. Or take the following 8 line-stanza from the long, Scottish ballad Hardyknute, that possesses a very similar metric and narrative tone of voice:

Full thirteen sons to him she bore,

All men of valour stout:

In bloody fight with sword in hand

Nine lost their lives without:

Four yet remain, long may they live

To stand by liege and land;

High was their fame, high was their might,

And high was their command.4

Just like any other poet of his time, Wilde will certainly have known and remembered famous English poetic ballads such as The Rime of the Ancient Mariner or A Shropshire Lad, but it seems much more likely that for the form and atmosphere of his prison-ballad about the shocking execution of Wooldridge he was influenced by his recent reading of Percy’s collection. The exemption from hard labour-tasks in his last months at Reading, thanks to major Nelson, must have given him even more time to peruse these ballads.

A last indication in this direction can be derived from a letter of 2nd June 1897 to Lord Alfred Douglas, in which Wilde at length shares his thoughts about the poetic form of the ballad, and expressly mentions an exemple from Percy’s collection (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 874). «All this is to beg you to write ballads», concludes Wilde, perhaps seeking emulative support from his lover and fellow-poet, who himself had repeatedly used the ballad-form in the past (Perkin Warbeck, Jonquil and Fleur-de-lys and – more recently – The Ballad of Saint Vitus (DOUGLAS 1919: 27, 39, 74).5

The ballad

As can be deduced from Wilde’s published correspondence, the first draft of The Ballad of Reading Gaol was written in not more than a few weeks’ time. A mere fortnight after his previously quoted announcement («Tomorrow I am going to write my poem») Wilde writes on 20th July 1897 to Robert Ross: «The poem is nearly finished» (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 915). Early August he even writes in the past perfect tense: «I have written a long poem» (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000 922). On the 18th of that same month he is less emphatic: «I have not yet finished my poem, but hope to do so soon» (HOLLAND/HART-DAVIS 2000: 926). And in subsequent days he refers consecutively to the poem as being «nearly finished», «unfinished up to today» and «still unfinished» (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 927, 928, 929/930).

What the author up to that moment has more or less completed are the first four of the ultimately six sections of the ballad.6 Section I in 16 stanzas tells the story of a condemned prisoner who has murdered his beloved wife. In section II, consisting of 13 stanzas, the day of the execution approaches, something that weighs heavily on the hearts of the other prison inmates. Section III (with initially 22 stanzas) describes the long night of waiting for the sun to rise and for the execution to take place. The grave in which the body of the executed murderer will rest, has already been dug. Finally, the 23 stanzas of section IV tell of the dreary and hurried burial of the hanged man and of the weariness among the other prisoners who are left to continue their unhappy existence.

Writing from Dieppe on 25th August 1897, Oscar Wilde sends the handwritten manuscript of this substantial first draft – just over half the length of the finished poem – to his publisher Leonard Smithers, with precise instructions on how it should be typed («good paper, not tissue paper») and bound («in a brown paper cover»). He writes: «It is not yet finished, but I want to see it type-written. I am sick of my manuscript» (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 931).

The truth is that Wilde was not only sick of his manuscript, but that both in his poem and in the reality of his life, three months after having regained his freedom, he was completely stuck. «I’m not in the mood to do the work I want,» he euphemistically writes to the painter William Rothenstein (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 930).

First of all, this had everything to do with the final break-up of his marriage and what he now knew to be a definitive separation from his two sons, aged 12 and 10. It is not easy to distinguish cause from effect, but more or less simultaneously a reunion was imminent with Lord Alfred Douglas, whom Wilde had not seen since 23rd April 1895 (MURRAY 2000: 82). Such a reunion would inevitably mean forfeiting the weekly allowance of £3 from his wife, that being Wilde’s only regular income at the time.

This was the practical and psychological constellation under which, in the weekend of 28/29th August the long-awaited reunion between Wilde and Douglas took place in Rouen. «My only hope of again doing beautiful work in art is being with you,» Wilde wrote to him afterwards (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 932/933). In one of his no less than three autobiographies Douglas described the weekend in equally idyllic terms: «We walked about all day arm in arm, or hand in hand, and were perfectly happy» (DOUGLAS 1929: 152).

Next to this emotional reunion with Douglas, whose presence in his life was very much connected to his creative impulses, Wilde had run into seemingly unsurmountable difficulties in continuing his ballad. His literary credo had always been that art, and art alone, should be the driving force in the process of artistic creativity and that the realities of life were inherently uninteresting. But now he had to face the challenge of transforming the sordid, bare and miserable reality of prison existence into a work of art that would meet his own critical standards. He, who in the preface to his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray had declared: «To reveal art and conceal the artist is art’s aim»; he, the writer of highly artificial works such as The Sphinx and Salomé, of colourful fairy tales in The Happy Prince and The Pomegranate Tree and of brilliantly sparkling dialogues in social comedies such as An Ideal Husband and The Importance of Being Earnest; he now had to find the right place in a prison ballad for words like «latrine», «quicklime» and «scaffold,» and if possible make them rhyme! No wonder Wilde is as happy as a lark when as of old he succeeds in putting in a ‘purple passage’, like when he finds the right place in his poem for «the kiss of Caiaphas», as he proudly announces to Robert Ross (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 934).

On top of all this was the grey dreariness of the weather in the North of Normandy and the many English tourists in Berneval-sur-Mer, who not always responded kindly to his presence there. Writing from autumnal and chilly Dieppe on 6th September, he complains: «I cannot stay in the North of Europe; the climate kills me […] my last fortnight at Berneval has been black and dreadful, and quite suicidal» (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 935). On 13th September, having made his decision to go South, he continues his lament: «I leave here tomorrow for Paris, and will then I hope start for Italy, if I can raise the money. […] I cannot write here: the cold weather, the ennui, the dreary English, are all paralysing» (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 936).

Behind all these external reasons that Wilde offers for not being able to complete his ballad, there is not only the psychological dilemma of his break-up with his wife Constance or the emotional upheaval of his reunion with Douglas, but also a problem that has everything to do with writing about imprisonment as an autobiographical experience. Wilde almost addresses the issue himself when he writes to a correspondent about his unfinished poem: «[I] find it difficult to recapture the mood and manner of its inception. It seems alien to me now – real passions so soon become unreal – and the actual facts of one’s life take different shape and remould themselves strangely» (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 947).

Confinement

In my PhD-thesis Het uur der waarheid (The hour of truth), which carried the subtitle «Over de gevangenschap als literaire ervaring» (On imprisonment as a literary experience), I have analysed the various ways in which the experience of imprisonment, defined as «confinement in solitude by way of punishment», has been treated in nineteenth and twentieth century West-European literature. In particular, I compare the manner in which authors of autobiographical works (i.e. people who have been or still are confined themselves) treat this experience to the way in which writers of fictional literature (e.g. novels, stories and poems) are imagining imprisonment. To make this comparison as concrete as possible, I take three pairs of European writers, each time an autobiographical writer against an imaginative writer: Silvio Pellico versus Stendhal, Oscar Wilde next to Charles Dickens and finally the imprisoned German poet Albrecht Haushofer against his coeval, the Dutch poet Jan Campert, who imagined a death cell and a multiple execution in his ballad «De achttien dooden» (The eighteen dead). This threefold comparison leads me to the following conclusion:

In autobiographical prison literature the reader escapes together with the author from the temporary confinement of the prison experience, in imaginative prison literature the reader is confined together with the protagonist by the author, who deploys a variety of literary means to lock as it were the door of the imagined prison cell from the outside (ASSCHER 2015: 290/291).

With this dichotomy in mind, we can see more clearly what is happening to Oscar Wilde at this stage in the composition of The Ballad of Reading Gaol. The author, living in freedom again, wishes the reader to feel how terrible the daily prison existence was, for trooper Wooldridge, for the author himself and for their nameless fellow-inmates. Only then will the poem be an effective protest against the treatment of prisoners, against capital punishment, against the whole inhuman prison system. But the very act of leading the reader into the almost living reality of prison life confronts the writer with the impenetrable walls of his own recent and traumatic memories. Instead of drawing the reader further into the prison experience, as the poem demands from him, the writer wants nothing else than to forget, to escape, as fas as possible. No more English tourists in grey and rainy Dieppe: fly to the warm South, to Italy, where the sun and love and art may mend a poet’s broken life and help him complete a half-finished poem. And so via Paris he escapes to Naples, with Lord Alfred Douglas joining him on the way in Aix-en-Provence (STURGIS 2018: 648).

Dilemma

This brief analysis may offer some biographical and psychological background for the dilemma Wilde faced in continuing his writing of The Ballad of Reading Gaol, but his painful internal conflict can also be phrased in more literary terms. Reliving the grey and terrible realism of prison life as he had experienced it first-hand, culminating in the execution of Wooldridge, evoked in its turn as a counterreaction a romantic escapism. By the end of August, these opposing forces were paralysing Wilde’s literary creativity, causing him to exclaim that the sight of his own manuscript made him «sick». Would a typed version of what he had written sofar be a solution? Probably not, but still he asks Smithers for it, in the letter already quoted of 25th August, with which the author encloses 61 out of eventually 109 handwritten stanzas of the poem.7

Wilde’s creative dilemma manifested itself among others in his wrestling with the use of adjectives in the poem, as is illustrated by a letter to Robert Ross, in which he writes:

With regard to the adjectives, I admit there are far too many «dreadfuls» and «fearfuls». The difficulty is that the objects in prison have no shape or form. To take an example: the shed in which people are hanged is a little shed with a glass roof, like a photographer’s studio on the sands at Margate. For eighteen months I thought it was the studio for photographing prisoners. There is no adjective to describe it. I call it «hideous» because it became so to me after I knew its use. In itself it is a wooden, oblong, narrow shed with a glass roof.

A cell again may be described psychologically, with reference to its effect on the soul: in itself it can only be described as «whitewashed» or «dimly lit.» It has no shape, no contents. It does not exist from the point of view of form or colour (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 956/957).

This quote clearly shows that Wilde had a sharp eye for what you might call the «programmatic» conflict in the creative process at hand: was this ballad a pamphlettistic protest or was it a case of imaginative empathy? And who was to be the poem’s protagonist: the narrating poet, who himself had lived through it all, or the tragic Wooldridge who deserved more than an inglorious burial?

Undeniably, the author was willing to sacrifice historical accuracy to demands of the chosen poetic form and to a stronger, more general effect of his words. Take the first stanza:

He did not wear his scarlet coat,

For blood and wine are red,

And blood and wine were on his hands

When they found him with the dead,

The poor dead woman whom he loved,

And murdered in her bed.

In these six opening lines there are no less than four points on which the poem differs from the version of Wooldridge’s story related above. Wooldridge was not dressed in scarlet; his regiment’s tunic was blue. After killing his wife he was not found «with the dead», and there was no wine involved. Finally, Wooldridge did not kill his wife in her bed.

But all this was not the ssential problem in the completion of the poem, neither was it a question of just finding the right adjectives. The poet Wilde himself may have been dissatisfied with seemingly empty adjectives like «whitewashed» en «dimly lit» for the description of a prison cell, for the reader – then and now – they seem suggestive enough to characterise a scene of which naturally words can never transfer the intense reality. No, the true problem for Wilde in completing The Ballad of Reading Gaol lay in the choice of what literary scholars, in particular narratologists, call the «focalisation» of the narrative.

Art and divinity

The narratological concept of «focalisation», first developed by the French literary theorist Gérard Genette (GENETTE 1980: 161-211), makes us aware of the instance through which a story is perceived. Who is it that sees, looks and interprets? In the first stanza of Wilde’s ballad, for example, the perception of what takes place lies with the narrator. But in the fourth stanza it is not the narrator who observes, but an «I» who is also imprisoned and who observes the condemned man:

I walked, with other souls in pain,

Within another ring,

And was wondering if the man had done

A great or little thing,

When a voice behind me whispered low,

«That fellow ’s got to swing.»

In the first, unfinished draft of The Ballad of Reading Gaol, the version in which Oscar Wilde is stuck and that he sends to his publisher to be typed, the reader receives his information mainly through a narrating «I» who is himself a prisoner, sometimes enlarged to a more general «we», indicating all the inmates together who are watching their doomed fellow-prisoner. These observations alternate with facts related by the all-knowing narrator who already addressed the reader in the first stanza. He describes things that the «I» who is himself a prison-inmate cannot possibly see or hear or know. For example in the fourth stanza of section III of the poem:

And twice a day he smoked his pipe,

And drank his quart of beer:

His soul was resolute, and held

No hiding-place for fear;

He often said that he was glad

The hangman’s hands were near.

What Wilde was able to achieve after his arrival on 19th September 1897 in sunny Napels in the company of his beloved Alfred Douglas, was to liberate himself from the conflict between the two competing focalisations: the all-knowing narrator who describes Wooldridge’s fate, and the autobiographical «I» who is himself an inmate and who suffers the sordid daily reality of prison life.

In an attempt to escape this paralysing conflict Wilde succeeds in adding no less than 48 stanzas to the first draft of the poem. Apparently, the working conditions in Napels were ideal for a man of Wilde’s taste and temperament.8 During the first week they stayed in the (very expensive) Hôtel Royal des Étrangers, on the 25th they took up residence in a rented house, the Villa Giudice in the southwestern quarter of Napels called Posilippo. In these congenial and inspiring surroundings Wilde was able to make two decisive moves towards a completion of his ballad.

Firstly, in section III of the poem, in which the long night before the execution is depicted, he added eleven stanzas. In a full-blown poetic vision he describes the agitated and demonic dreams of the prisoners in their cells, until finally the morning sun throws its first rays through the barred windows and the fateful day of the hanging commences. These nightmarish images of wild dances and terrifying monsters and the exotic words he uses to describe them («rigadoon», «grotesques», «arabesques», «pirouettes», «marionettes», «masque», etc.) show us more than a bit of the old pre-prison poet Oscar Wilde. This is not just a narrator, but a romantic-decadent visionary and singer, a truly imaginative artist.

Secondly, he adds two sections to the poem, section V with 17 stanzas and a small concluding section VI of three stanzas. In these 20 added stanzas he distinctly rises above the position of the narrator in the first stanza. The poet who now speaks in the opening stanza of section V is a totally new voice:

I know not whether Laws be right,

Or whether Laws be wrong;

All that we know who lie in gaol

Is that the wall is strong;

And that each day is like a year,

A year whose days are long.

Here speaks a former prisoner who explicitly takes it upon himself to draw conclusions from the preceding story in the form of a rhymed and metrical protest against the inhumanity of the prison system, of any prison system. On the authority of his own lived-through experiences he pronounces that each man is guilty and that therefore no prison sentence can ever be justified and that every imprisonment leads to inhumanity. Thus the contrast between the «he» that has to die and the «I» who is doomed to witness this, is resolved by a superhuman, er even divine voice that elevates itself above an earthly human conflict. This ultra-human voice seems to derive at least part of its moral authority from the fact that its body has – like that of Christ on the cross – itself suffered in cell C.3.3. and so can speak on behalf of all sufferers.

Polishing

From the end of September to early December 1897 Wilde kept on making smaller and larger improvements on what was slowly becoming the final, 654-line version of the ballad. This process can be followed quite closely from the exchange of letters between author and publisher, that is also full of negotiations, quarrels and misunderstandings with regard to the contract, the advance and the serial rights in England and in America. Near the end, Wilde starts to doubt the dedication to «C.T.W.» Shouldn’t he give the dedicatee pseudonymous intials, e.g. «R.J.M»? But in the end he sticks to the historical facts (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS: 986).

Finally Wilde communicates on 11th December to Smithers: «I think you had better send me no more proofs of the poem. I have the maladie de perfection and keep on correcting. I know I have got it now to a fairly high standard, but I don’t want to polish forever» (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 1007). On 9th January 1898 he accepts stoically that the revision proofs he had been waiting for have evidently gone astray in the post to Napels, and he writes to his publisher: «to wait longer would be foolish. I am sure it is alright» (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 1010).

The Ballad of Reading Gaol was published as planned on Sunday 13th February 1898 in a first printing 800 plus 30 de luxe copies. Instead of the name of the author the title page states Oscar Wilde’s prison number at Reading: C.3.3. In the next four months more than 5.000 copies in English alone would be sold, and it is no exaggerationen to call The Ballad of Reading Gaol Wilde’s most lasting and emblematic work. It has been continuously in print ever since its first publication, in countless editions and translations.9

On the day of publication Wilde returned to Paris. Encouraged by the immediate success of his long poem, he soon wrote his second letter to the editor of the Daily Chronicle, about the points on which the English prison system in his view badly needed to be reformed. The article appeared under the heading: «Don’t read this if you want to be happy today» and it was proudly signed by «The author of The Ballad of Reading Gaol» (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 1045). The piece was published on 24th March, on the eve of a parliamentary debate in the House of Commons on the new Prisons Act of 1898, in which several of the improvements Wilde had advocated were indeed included.

Two and a half years later, Oscar Wilde died in Paris, on 30th November 1900. His tomb on the cemetery of Père Lachaise, erected nine years after his death, continues to be a place of pilgrimage for all those who feel in some way connected to his work and his life.

Conclusion: synthesis

Was Oscar Wilde correct in assuming, during a temporary writer’s block, that his long poem about the prison in Reading suffered from a «divided aim»? That the realistic and the romantic element are mututally exclusive? That poetry and propaganda do not go together?

If one looks at the rest of Oscar Wilde’s poems, with their highly artificial idiom and mostly aesthetic themes, one can readily understand that initially the author held himself incapable of writing a poem in which a latrine, a scaffold and a white-washed cell would be the main pieces of scenery. But looking back on this ballad from the present and seeing how Wilde, a mere six weeks after his release from prison, first succeeds within a few weeks’ time to put 61 stanzas of the poem on paper, and then, reunited with his lover in Napels, to give the poem with an additional 48 stanzas an overarching unity and completion, cannot but concede that the ‘divided aim’ – if there ever was such a dilemma – has been solved by the author in a accomplished synthesis. The Ballad of Reading Gaol shows that one poem can very well serve two aims, can transform an antithesis into a synthesis, can combine personal experiences with literary expression, reconcile protest and poetry. Surely, these are truths that no genuine lover of poetry would dare to challenge.

Bibliography

ASSCHER, M., Het uur der waarheid, Amsterdam, Atlas Contact, 2015 (for English language summary. See: Online

BECKSON, K., (Ed.), Oscar Wilde. The Critical Heritage, London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1970.

BRISTOW, J., & MITCHELL, R.N., Oscar Wilde’s Chatterton. Literary History, Romanticism, and the Art of Forgery, New Haven, Yale, 2015.

DOUGLAS, A., The Collected Poems of Lord Alfred Douglas, London, Martin Secker, 1919.

DOUGLAS, A., The Autobiography of Lord Alfred Douglas, London, Martin Secker, 1929.

ELLMANN, R., Oscar Wilde, London, Hamish Hamilton, 1987.

FRANKEL, N., Oscar Wilde.The Unrepented Years, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 2017.

GENETTE, G., Narrative Discourse, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1980.

HOLLAND, M., & HART-DAVIS, R., (Ed.), The Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde, London, Fourth Estate, 2000.

HORODISCH, A., Oscar Wilde’s Ballad of Reading Gaol, New York, Aldus Book Company, 1954.

KOHL, N., The Works of a Conformist Rebel,Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1989.

MONTGOMERY HYDE, H., Oscar Wilde. The Aftermath, London, Methuen, 1963.

MURRAY, D., Bosie. A Biography of Lord Alfred Douglas, New York, Hyperion, 2000.

MASON, S., Bibliography of Oscar Wilde, London, T. Werner Laurie, 1914.

PERCY, T., Reliques of Ancient English Poetry, London, James Nisbet and Company, 1906.

STOKES, A., The Pit of Shame, Winchester, Waterside Press, 2007.

STONELEY, P., «Looking at the others: Oscar Wilde and the Reading Gaol Archive», Journal of Victorian Culture, n. 4, 19, (2014), p. 457-480.

STURGIS, M., Oscar. A Life, London, Head of Zeus, 2018

WILDE, O., The Ballad of Reading Gaol, London, Leonard Smithers, 1898.

WILDE, O., The Ballad of Reading Gaol, London, Methuen, 1910.

WILDE, O., The Ballad of Reading Gaol, in B. FONG, K. BECKSON, The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Vol. 1, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2000.

YEATS, W.B., Oxford Book of Modern Verse. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1936.

Websites

http://www.eastgarston-pc.gov.uk/The_Parish/The_Ballad_of_Reading_Gaol.aspx

https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2014/oct/16/reading-jail-oscar-wilde-lover-photograph

Illustrations and captions for MAARTEN W.B. ASSCHER, A Divided Aim

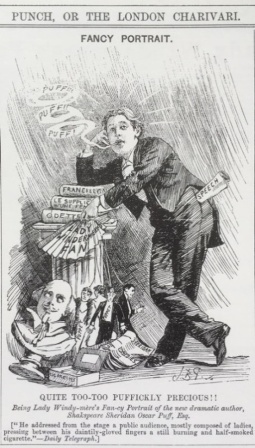

Oscar Wilde as a successful playwright in 1892, in a cartoon from the satirical magazine Punch.

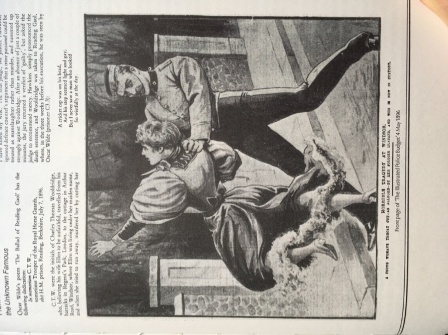

The murder of Laura Ellen ‘Nell’ Glendell, as pictured on the frontpage of The Illustrated Police Budget.

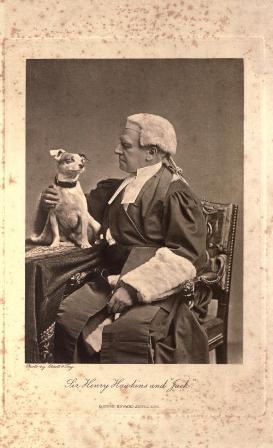

Justice Sir Henry Hawkins, later Baron Brampton, who pronounced Wooldridge’s death sentence. He poses here together with his favourite dog Jack. In 1894, the dog was mysteriously poisoned with strychnine by someone who apparently hated the judge very much.

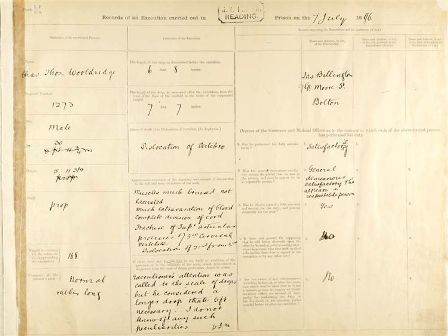

The official report of the execution of Charles Thomas Wooldridge on 7th July 1896.

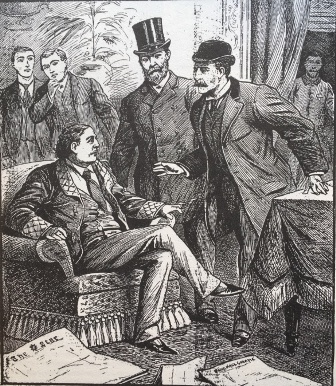

The arrest of Oscar Wilde in the Cadogan Hotel on 5th April 1895, as visualised in The Illustrated Police Budget.

Reading Prison seen from the South.

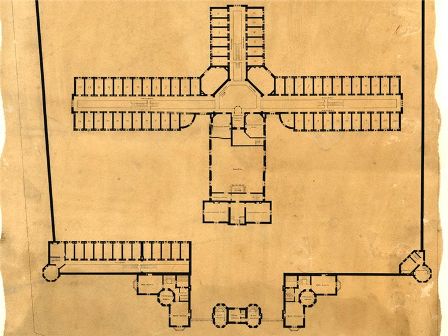

The layout of Reading Prison, clearly showing the wings A, B and (to the left, i.e. to the West) C.. Each wing consisted of three floors or galleries. Oscar Wilde was in the third cell on the third floor of the C-wing, hence his prison number C.3.3.

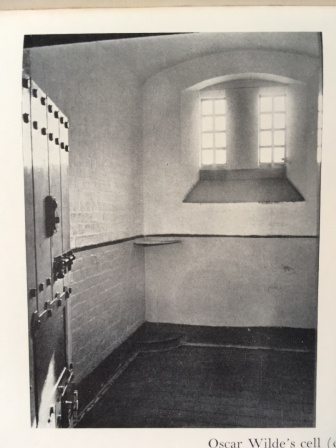

Oscar Wilde’s cell in H.M. Prison in Reading.

Henry Bushnell, who was imprisoned at Reading simultaneously with Oscar Wilde. After his release Wilde corresponded with his erstwhile fellow-inmate.

The Hotel de la Plage in the coastal village of Berneval-sur-Mer in normandy, where Oscar Wilde stayed during the first weeks after his release from prison in May 1897.

The Café Suisse in Dieppe, to the left under the arcades, where Oscar Wilde regularly sat and wrote in the summer of 1897, after his release from prison.

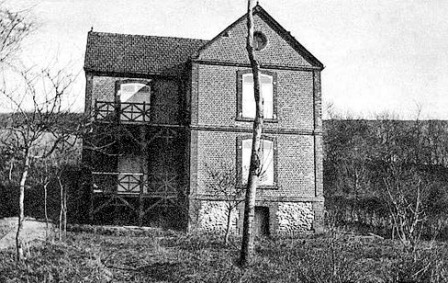

The Chalet Bourgeat in Berneval-sur-Mer, where Oscar Wilde started writing The Ballad of Reading Gaol on 8th July 1897.

Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas in Napels in the autumn of 1897.

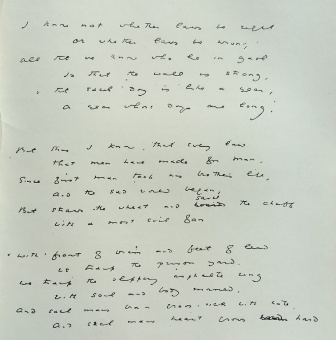

The author’s manuscript of the three final stanzas of The Ballad of Reading Gaol.

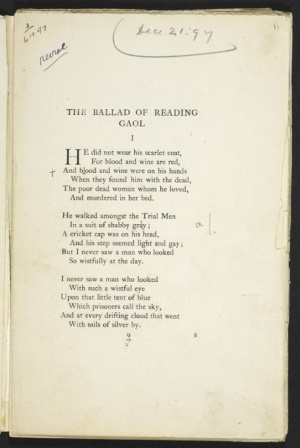

Proofs of the first page of The Ballad of Reading Gaol, with corrections in the author’s hand..

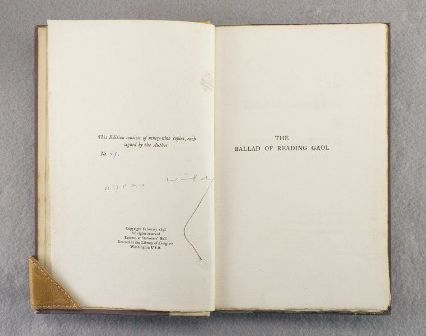

A copy of the third edition of The Ballad of Reading Gaol, published one month after publication of the first edition, in a printing of only 99 humbered copies, signed under his own name by the author.

Note

↑ 1 Unfortunately no mugshot of Oscar Wilde survives, although the criminal archives of the County of Berkshire have yielded such photos of several of his contemporaries at Reading prison.

↑ 2 Although Wilde writes to Robert Ross on 31st May/1st June 1897: «I have begun something that I think will be very good» (HOLLAND, HART-DAVIS 2000: 869), the editors of Wilde’s correspondence too rashly assume that this «something» is what ultimately became The Ballad of Reading Gaol. Especially the fact that in over five weeks’ time, in more than 50 letters and postcards to fifteen different correspondents (of which seventeen letters and postcards to Ross), Wilde subsequently does not refer again, not even once, to this «something», calls for more caution in assuming that the author had already begun writing his prison ballad in late May. It is therefore to be regretted that the editors of Volume 1 of The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde (WILDE 2000: 331), without any further reference or proof accept the same assumption. The same goes for Matthew Sturgis in his otherwise excellent biography of Wilde (STURGIS 2018: 637). According to Frankel, Wilde started writing the poem at the end of May (FRANKEL 2017: 102). On the authority of Lord Alfred Douglas Frankel even states that Wilde «conceived the idea and maybe even the first few stanzas of the poem in prison, although he did not put pen to paper until after his release» (FRANKEL 2000: 321). For all these speculations there is no evidence whatsoever, and they are in contravention of a statement from the author himself, written on the first anniversary of Wooldridge’s execution.

↑ 3 PERCY 1906: 255. The spelling of the English has been modernised.

↑ 4 PERCY 1906: 348, equally in modern English spelling.

↑ 5 If Wilde had already started writing a new ballad of his own, he would certainly have mentioned the fact to Douglas. He may already have been toying with the idea, but there is no evidence for him putting pen to paper before early July. See note 2.

↑ 6 For a detailed and thorough literary analysis of The Ballad of Reading Gaol, see: KOHL 1989: 290-307.

↑ 7 The first version in 61 stanzas was included by Robert Ross as an appendix to his 1910 reprint-edition of The Ballad of Reading Gaol (WILDE 1910: 63). In his introduction Ross explicitly calls this short version ‘the original draft of the poem’, so that we may assume that he possessed or at least had seen a handwritten or typed version of the same.

↑ 8 In his detailed reconstruction of Wilde’s final years, after his release from prison, Frankel calls the author’s reunion with Douglas ‘ill-fated’ (FRANKEL 2017: 130). There are certainly good biographical reasons for using that epithet, but for the completion of The Ballad of Reading Gaol, one of Wilde’s most lasting literary works, the contrary seems to be true.

↑ 9 The most authoritative bibliography of the poem is HORODISCH 1954, though unfortunately after its first publication it was never updated.