Living Things in the Extractivist Ruins. Diana Lelonek in Conversation with Jakub Gawkowski

Abstract

This dialogue explores the multifaceted relationship between artistic practice, environmental discourse, and personal memory through the lens of Polish visual artist Diana Lelonek’s work related to the post-industrial and post-extractivist landscapes. In conversation with curator Jakub Gawkowski, Lelonek reflects on her upbringing in Dąbrowa Górnicza in Dąbrowa Basin, revealing its profound impact on her sensibilities and thematic exploration. Emphasizing the interconnectedness of human and non-human entities, Lelonek delves into her engagement with the Anthropocene and the redefinition of nature within a post-industrial context and landscape transformation. The dialogue allows for an examination of the development of Lelonek’s practice, her celebration of the resilience of ruderal flora, as well as negotiation of dualities. Through a critical lens, the conversation interrogates populist and nostalgic narratives about natural environment, highlighting the complexities of human-nature entanglements.

Jakub Gawkowski: Diana, I would like to discuss how your artistic practice related to the Anthropocene connects to your background and to the industrial and post-industrial region of Upper Silesia and the Dąbrowa Basin. We have been exploring this connection for some years now, given our mutual interest in this region. However, it seems that in your practice, the concept of locality isn’t prominently featured as an interpretive framework. Your art has often had a universal appeal, addressing the planetary environment in a way that seems detached from any specific locale. This is evident in projects like the Center for the Living Things (2016-ongoing) or Zoe Therapy (2015–16) that both challenge anthropocentrism and modern nature-culture dichotomy. I’m curious about the extent to which your focus on redefining the notion of nature and on the relationship between humans and other species is influenced by your background. Can you describe how you became interested in this topic, and whether it’s linked to your personal experiences?

Diana Lelonek: The two are completely intertwined; my art is deeply rooted in my upbringing. I realized this only recently. My work naturally gravitates towards themes of nature and the interactions between human and non-human entities, seemingly stemming from my interests. But at some point, I began questioning why I was drawn to these topics, especially to the desolate, toxic landscapes of post-industrial areas. Then it struck me: my upbringing in Dąbrowa Górnicza had a profound influence on my perception of nature and my sensitivity to such environments. Spending time in these landscapes, witnessing their beauty and decay, shaped my artistic sensibility.

Jakub Gawkowski: How were these landscapes part of your upbringing?

Diana Lelonek: I come from a workers’ estate near the “Katowice” Steelworks, I saw this monumental construction through the window my whole life. It’s the largest steel-producing conglomerate in Europe. Sometimes it smelled like rotten eggs. Then my mom would say, “Close the window because today the wind isn’t blowing towards Krakow, it’s blowing towards us.” Usually, the wind blew towards Krakow and that’s where most of the pollution from the factory fell. But when it occasionally blew in our direction, it smelled terribly. There were very beautiful, romantic sunrises in various colors; the sun rose behind the factory’s pollution. Besides the factory, there was also the inactive Paryż coal mine in Dąbrowa, where you could go inside and explore the abandoned premises. We also used to go to Gołonowska Hill, where there was a meadow, and a view of the factory’s blast furnace. When we sat there in the evenings with friends, you could see the fire. It was amazing: you sat in the meadow, looked at the stars, and in front of you was this huge, burning furnace.

Jakub Gawkowski: You mentioned wastelands, overgrowth, nature reclaiming the land. The visuality of your art can also be connected to this region.

Diana Lelonek: Dąbrowa Górnicza, and the regions of Upper Silesia, and the Zagłębie Basin are associated with coal, blackness, dirt. However, these are very green areas, although it’s not ideal, clean greenery, but living in relation to the industrial landscape. Dąbrowa Górnicza is one of the greenest cities in the region. There are beautiful lakes that are on former sand quarries, which are also post-industrial, in fact a quite decent ecosystem has developed there. One of the lakes is partially protected because there are nesting places for birds now. For a long time, I didn’t know any other nature, any other place, so I never understood the difference between artificial and natural; it always seemed strange to me. Nature, which is “pure” and conventionally considered more valuable, didn’t attract me much. There is so much more to discover in such post-industrial areas. There is also the Błędowska Desert, which is now a reserve. The desert was created after mass deforestation, and now they let it overgrow and cut down trees to maintain this desert system. Everything is intertwined in multiple layers and the motifs in my works can actually be found in my childhood. The fact that Dąbrowa is called Dąbrowa comes from the oak forest that was in the region and was cut down. However, the forest where I spent most of my time was a birch grove because birches typically take root in such poor, post-industrial soils. But is a birch grove worse than an oak one?

Jakub Gawkowski: When did these threads - locality and interest in planetary changes – started to come together for you?

Diana Lelonek: I went back to Dąbrowa Górnicza to take some photos for the project Yesterday I Met a Really Wild Man (2015), and one of them featured the steelworks - the same one I would see from my window throughout my childhood. That’s when I finally understood that where I come from is consistent with what I do. I returned to a place that shaped my perception of nature, and feelings. This going-away-and-coming-back was one of my first conscious artistic projects. That’s when I also became interested in theoretical discussions related to the Anthropocene, to eco-criticism, and in reworking the understanding of nature. Before that, I didn’t have this theoretical background, but I was intuitively drawn to similar reasoning threads. When I started reading Timothy Morton’s Dark Ecology, I knew that’s exactly it! Because of my background, I’ve always understood nature in this way, although I was not able to name and turn it into discourse at first.

Jakub Gawkowski: We’re talking about the relationship of your practice to this landscape, which can’t easily be classified as natural. Thinking about your art and the stakes it takes on nature, I wanted to draw your attention to other threads in Dąbrowa Górnicza’s history - the sudden development of industry, changes in the name of modernization, and migration - the city was developed by people coming from other parts of Poland to work. In this context, I’m also thinking about the notion of change. In a broader perspective, your art tells of the Anthropocene era and planetary transformation. Living in Dąbrowa in the 1990s, you observed the transformation of the landscape but also an economic transformation, its entry into capitalism.

Diana Lelonek: The whole city was built as everyone came from somewhere else, my family too. For many, moving to work in Dąbrowa was often a way to escape from the countryside and a chance for social mobility. My dad came to Dąbrowa from a village near Biłgoraj in Eastern Poland; he completed his studies, and got a job at the Huta Katowice. While I was growing up, in the 1990s, a political transformation took place, and a lot started to deteriorate there. Many workplaces were privatized and closed down, people lost income and stability.

Jakub Gawkowski: Your family history, which is also the history of many other families in the region, is also related to something that appears in your practice, namely the themes of movements, migrations and displacements of human and non-human actors. Both your parents are from Biłgoraj, right?

Diana Lelonek: Not exactly. There are more movements and directions in this story. My mother always emphasized that she was born in Silesia and she spoke of Dabrowa and the whole region of Zagłębie, as a place where no one has roots, just a patchwork of newcomers who came for work. She really disliked the block of flats where we lived. But while she always said she was from Silesia, later on I discovered that her parents, that is my grandparents, were from Lesser Poland - they were teachers who were brought in to teach Polish to Silesians. Teachers were sent to Silesia and the recovered territories to Polonize the population. So, my mother’s family wasn’t from Silesia at all, but that identity became deeply ingrained there. And my dad was just in from a village near Bilgoraj and benefited from the communist policy that privileged those originating from the countryside. As a result, he was granted upward mobility and was able to study at University - the first of his family. Both of my parents graduated from the Polytechnic. The steel mill offered very good options at the time and that is why they started living in Dąbrowa.

Jakub Gawkowski: Do you think this background also shaped your understanding of locality?

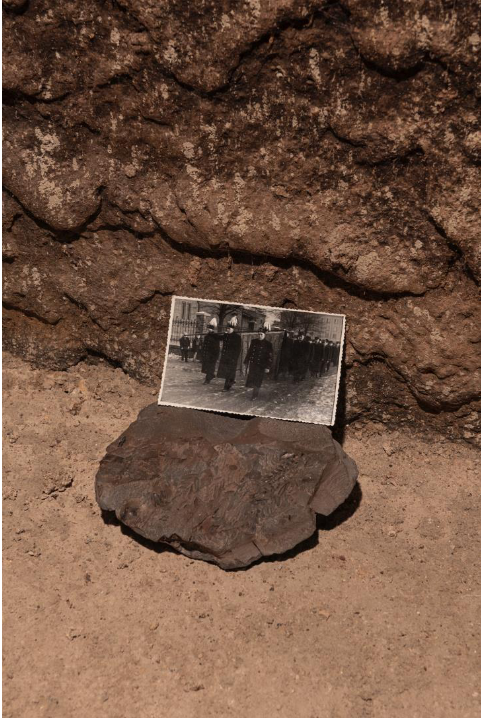

Diana Lelonek: I’ve been thinking about it lately too: why do these stories of displacement, loss of home touch me so deeply? Indeed, the whole Dąbrowa Górnicza is constructed like that, everyone there is a newcomer. Everyone came to work at the Katowice steelworks or the Paryż coal mine. I’ve been wandering my whole life, often moving from place to place. I also don’t have my own place because I work in the arts, I don’t have family financial support and can’t afford my own apartment. I started exploring these themes of change and searching for a place intuitively, until it eventually became part of my practice. In 2021, together with Mateusz Krzesiński and Monika Marciniak, we created “Buried Landscape”: it’s an archive of spoken, textual, and visual stories and memories of former town residents who had been displaced by brown coal mines in the areas of Greater Poland, Lower Silesia, and Bełchatów.

Jakub Gawkowski: It’s fascinating how the trajectory of your practice, shifted from ignoring or even programmatically erasing the presence of humans to focusing first and foremost on other organisms. Subsequently, you reached a point when you focused your attention on the human perspective. The exhibition “Buona Fortuna” at Fondazione Pastificio Cerere in Rome in 2020, which we prepared together, addressed and connected these different perspectives and scales: the planetary-ecological purview alongside the human narrative, wherein mining figures prominently features as a vestige of tradition and folklore. As far as I am concerned, embracing these two perspectives has a vital role in bridging the gaps in public discourse. Unfortunately, I feel like too often the activist-ecological discourse is polarizing, and miners are seen as environmental exploiters vis-à-vis others who play as champions of conservation. But these are communities whose lives depend on coal mining and are involuntarily involved in the degradation of the natural environment. You have experience of living and working in the post-extractivist regions, working with communities, collecting stories, but you also have experience in local and trans-local activism, and finally international artistic practice. The climate crisis is usually discussed on a grand scale, which is difficult to connect with what is happening locally. So, what stories should we tell to nuance this perspective?

Diana Lelonek: Many people, also in the arts, tend to think simplistically and somewhat discriminatively, frankly speaking. When I presented my art in Western Europe, in such an ecological context, I often hear comments like, “Oh, Poland, oh my, you pollute the most, the highest CO2 emissions.” This exoticizes these regions and flattens the problem. That’s why I prefer to do projects where I refer to the Polish local context, which I know well, and to speak about the local area I am more familiar with and have a deeper insight into. At a later stage, this can be a starting point to deal with more universal issues, but I first need to move from something I know well. It can also be some personal perspective because it is important for such stories or her-stories, merging from personal experience, to be able to exist. Take for example, the “Buried Landscape” archive – I have the feeling that such work can offer a different understanding than a research conducted by companies commissioned by Greenpeace. The latter work is equally important, but direct conversation with people and narrating and depicting the stories of those affected by coal mining is extremely valuable.

Jakub Gawkowski: How then do you or should the perspectives of human and non-human beings be conjugated? You mentioned a green landscape that is not “pure” - how do these experiences you talk about translate into your understanding of art?

Diana Lelonek: Sometimes I have the impression that now people fall into the trap of aestheticization too easily. Ecological aesthetics is fashionable, but conspicuously marked by its penchant for nature’s romanticization. While the cultivation of empathy and affective resonance is undeniably commendable, this rhetoric creates a trap as we lose sight of all these entanglements, as is visible in Silesia: intricate confluence of industry, nature, and humanity.

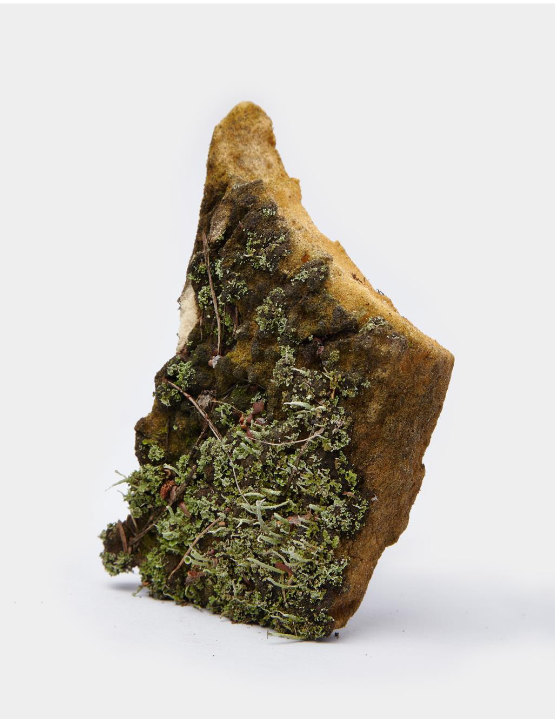

If we are dealing with such complex networked and intertwined narratives, it is not possible to suddenly think either about nature only or about industry only. That’s why in my works, I always look for such spaces and take up such topics that are semantically entangled and complex. I prefer to show entanglement rather than provide easy answers and put forward simple theses. I prefer to talk about entanglement. That’s why I’ve always found it hard to tell people more about some of my projects, because I felt that they wanted a simple and quick answer. While some people may gravitate towards simplistic interpretations of the Center for the Living Things positing it as an affirmation of nature’s triumph, for me its essence is far more nuanced. The Center embodies an ongoing, symbiotic relationship between botanical specimens and anthropogenic artifacts: there is an ongoing, ever-changing relationship and a somewhat indomitable spirit sort of dialectics between those animate and inanimate entities.

Jakub Gawkowski: What you’ve just said about the idealization of nature and its re-romanticization finds resonance within populist rhetoric, which oftentimes extols a return to an imagined past. The emblematic slogan “Make America Great Again” epitomizes this tendency, wherein a fictitious past is invoked to satiate contemporary exigencies. Similarly, the notion of a pristine, pre-modern symbiosis between humanity and nature is symptomatic of this proclivity. Hence, the history of Upper Silesia and Dąbrowa Basin serve as a poignant counterpoint, underscoring the inherent complexity of human-industrial-natural interrelations.

Diana Lelonek: All these practices of returning to nature, workshops in the forest, hugging trees, forest baths, are very pleasant and valuable for mental and physical well being. But I wonder whether they are also responses to the crisis, which by the way are also created by market-capitalist logic. Yet, the intricacies of ecological entanglement remain conspicuously unaddressed, effaced beneath the veneer of nostalgia. This proclivity towards binary oppositions obfuscates the intricate tapestry of relationships which characterize the landscapes we talk about. It’s a kind of populist solution as it provides simple answers. It allows people to more easily escape from the overwhelming fact of toxicity, from what Timothy Morton called Hyperobjects. We can temporarily push their stickiness away and remove them from sight. But it’s becoming increasingly more difficult to do so, in spite of us living in privileged countries where you don’t see this pollution every day. Warsaw has huge smog issues, but it’s nothing compared to pollution in other parts of the world. We still live in a privileged country in this respect; we can also escape a bit into this wellness.

Jakub Gawkowski: So, is it easier to go back to nature as a form of escapism, and to treat it as a particular form of show?

Diana Lelonek: Yes, that’s one perspective, but if you live, for example, in Dąbrowa Basin, then you can’t do it that easily. It’s not easy to forget about this entanglement, even if nature is a source of relaxation and pleasure. Lake Pogoria is beautiful, but excavators and small machines lie underwater at its bottom. Something similar can be found anywhere, sometimes it’s difficult to perceive such complexity. That’s why I have a problem with treating nature as escapism. These are also problems in ecological thinking. I am surprised by the sort of hierarchical thinking according to which one sees one natural context has higher or better than another one, that certain areas are worth protecting while others are not. Well, then a natural forest, is more valuable than a forest growing on degraded land. But the latter is in fact super-resistant and must be resilient to regenerate in such very depleted and degraded land. Why should such birches, for example, be regarded as less valuable. Are they less worth because born out of regenerated or degraded lands? And if trees or plants belong to a less contaminated natural context, say nature in its prime, then they are more valuable by default? This reasoning has always triggered a strong feeling of disagreement within me. In my understanding and perception, these ruderal plants, which have regenerated on these degraded lands, are a kind of superheroes and resilient workers, simply they are living in precarious conditions... How much strength they must have to prepare this ground for the next species, what is more demanding? It’s really some enormous work they put into their growth. They are not appreciated, just like human workers who do basic tasks. Their role is diminished because, conventionally, they are not beautiful and not attractive for tourists, that is, they are not true nature. Not only do they work really hard, but their work is completely invisible. I like to see them as heroic workers.

Taking walks in post-industrial areas is such an extraordinary lesson to be learnt. By entering the area of a closed mine, you can see and learn a lot about the typical nature found in the wastelands and take a closer look at these areas. By this direct experience, you can somewhat demystify the idea that the historical presence of any industry automatically means no life at current time. This helps to understand that everything functions in a continuum.

* * *

Diana Lelonek is an artist working in Warsaw, Poland. Graduated from the department of Photography at the University of Art in Poznan (PL). PhD at Interdisciplinary PhD Studies, University of Art in Poznań. Currently, she is running the Artistic Research Studio at the Artistic Research and Curatorial Studies Department, Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. Diana Lelonek explores relationships between humans and other species. Her projects are critical responses to the processes of over-production, unlimited growth, and our approach to the environment. She uses photography, living matter, and found objects, creating work that is interdisciplinary and often appears at the interface of art and science. She participated in several international exhibits, festivals and group shows at: Edith-Russ-Haus for Media Art, Oldenburg; Kunstraum Niederösterreich, Vienna; Temporary Gallery, Cologne; Tallinn Art Hall; Museum of Art in Łódź; Culturescapes Festival, Basel; Musée de l’Élysée, Lausanne; Dorothea von Stetten Award, Kunstmuseum Bonn; Tinguely Museum, Basel; Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Warszawa; LCCA, Riga; A.I.R Gallery, New York; Sapporo Art Festival, NTU Center For Contemporary Art, Singapore.

Jakub Gawkowski is an art curator, writer, and a PhD student at the History Department of Central European University in Vienna. His curatorial practice explores themes of memory, forgetting, knowledge and ignorance. He recently curated, among others, The Work That Textile Does (with Marta Kowalewska and Anne Szefer Karlsen, Central Museum of Textiles in Łódź, 2023); Wacław Szpakowski. Riga Notebooks (with Inga Lāce and Daniel Muzyczuk, Latvian National Museum of Art, 2023); Erna Rosenstein, Aubrey Williams. The Earth Will Open Its Mouth (Muzeum Sztuki, 2022); The Earth is Flat Again (Muzeum Sztuki, 2022). Together with Marysia Lewandowska, he co-edited a volume of selected critical writings by Ewa Mikina. His essays and interviews were published in, among others, Krytyka Polityczna and e-flux. He is a board member of the QueerMuzeum in Warsaw and Trafo Centre for Contemporary Art in Szczecin, and a member of AICA.