The Supernatural Thrilla from Manila: How Budjette Tan and Kajo Baldisimo's Trese Took Filipino Komiks, Comic Arts, and Culture Global

Abstract

Francese | IngleseD'abord une œuvre de niche dans les « komiks » philippins, la série noire surnaturelle de Budjette Tan et Kajo Baldisimo, Trese, a été acclamée à l'échelle internationale et a fait l'objet d'une adaptation animée sur Netflix en 2021. Bénéficiant d'une position unique aux confins de l'Asie du Sud-Est, de l'Asie de l'Est et du Pacifique, et culturellement entre l'Est et l'Ouest, les Philippines possèdent une riche tradition graphique qui reflète la diversité de ses peuples et de son histoire. Profondément ancrée dans la mythologie culturelle philippine et illustrant les questions d'actualité dans le cadre urbain trépidant de Manille, la série Trese de Tan et Baldisimo constitue un modèle fantastique pour l'exploration spéculative de la société, des traditions et des arts de la bande dessinée philippins, et elle est tout à fait capable d'exporter cette exploration vers des publics philippins et non philippins à l'étranger. En utilisant la série comme étude de cas, j'explore le succès et la portée de Trese en tant que référence potentielle pour ouvrir la porte à la représentation de plus d'œuvres des Philippines et d'autres régions du monde avec des traditions de bande dessinée sous-discutées.

When the sun sets in the city of Manila, don’t you dare make a wrong turn and end up in that dimly-lit side of the metro, where blood-sucking aswang run the most-wanted kidnapping rings, where gigantic kapre are the kingpins of crime, and magical engkantos slip through the cracks and steal your most precious possessions. When crime takes a turn for the weird, the police call Alexandra Trese. (TAN and BALDISIMO Trese Vol. 1: Murder on Balete Drive Back Cover and Trese Vol. 5: Midnight Tribunal Loc 6)

As a medium both defined and confined by its use of frames, comics have shown a remarkable capacity for not only for exceeding the boundaries of their traditional ink-stained panels but also challenging the way and type of stories that are told across global geopolitical borders. Following the earlier international spread of American comics and Franco-Belgian bande dessinée, the late 20th century and early 21st century explosion of Japanese manga across global sequential art shelves proved that non-Western comics traditions could also capture the hearts and minds of readers far beyond their domestic shores. In the 2020s, as the global media landscape becomes increasingly diverse and transmedia in scope, the question remains as to whether comics traditions from under-represented regions of the world can see their works gain appreciation by home and global audiences alike.

To examine this possibility, I will conduct a case study on the Filipino “komiks” series Trese written by Budjette Tan and illustrated by Kajo Baldisimo. Originating as a relatively niche work in the Philippines before achieving domestic recognition and success (Manansala 1), this supernatural noir series would receive international attention and acclaim, eventually seeing adaptation into a Netflix series in 2021. Situated on the eastern fringes of Southeast Asia—not far from the southern limits of China, Japan, and Korea—and with a long history of first Spanish and then US colonialism, the Philippines have a unique transnational position, particularly as outside cultural and political influences continue to compete for attention in the archipelago nation and its massive Filipino diaspora continues to spread globally. As a series of islands with a long history of isolation, the country itself is a varied mix of different cultures, languages, belief systems, and native storytelling traditions. With its deep roots in Filipino cultural mythology and representations of current ongoing issues in the pulsing urban setting of Manila, Tan and Baldisimo’s Trese serves as a fantastic model for the speculative exploration of Filipino society, traditions, and comic arts, and one that is more than capable of exporting that exploration to both Filipino and non-Filipino audiences abroad (Cayton). To this end, my goal in this study is to explore the success and reach of Trese as a potential benchmark for opening the door to representation of more works from the Philippines and other regions of the world under-discussed in global comics.

For most international audiences, their first exposure to Trese—and by extension the world of Filipino komics in general—likely came through the Netflix animated series based on Tan and Baldisimo’s komic. Soon after its release in 2021, the first season charted in multiple countries around the world and reached the top 10 in TV show rankings in almost 20 countries. In its native Philippines, it quickly and unsurprisingly established itself as number 1 (Ichimura). While Netflix and other streaming services are notorious about keeping the overall viewership numbers of shows tight to their chests, these results are a strong indication of both domestic and international interest in the supernatural noir heavily rooted in Filipino culture and mythology. Prior to its adaptation, Trese was not only an original property largely unknown outside of its home archipelago, but the first major Filipino animated series based on a komik to achieve this level of international popularity and critical acclaim. This success was achieved despite the relative lack of pre-existing familiarity of international audiences both with the source material and with Filipino culture and mythology, particularly in comparison to those of Japan or the West. At the time of writing, possibly due to production delays caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, Netflix had yet to officially confirm the release of a season 2, although there remains much online speculation about the possibility (WheNetflix). Nevertheless, the reach achieved by the first season can be considered a success, potentially paving the way for more Filipino komiks to be adapted for international audiences. There would be no animated series, however, without Tan and Baldisimo’s landmark original komik series.

While its domestic tradition of sequential art has never reached the financial heights and international interest of American comics, Japanese manga, or Franco-Belgian bande dessinée, Filipino komiks have had a significant presence in and impact on their home culture as they developed over the course of the 20th century. Their growth, however, has always come in the shadow of various foreign influences that had impacted Filipino culture over its history. While many Filipinos can trace their ancestry to the Austronesian migrants who arrived in the islands by 2200 BC, the islands did have some pre-existing peoples, such as the Negritos, and eventually developed into a range of diverse indigenous cultures many of which persist to this day (RAGRAGIO and PALUGA). With close geographic positioning to southeast Asia, trade links naturally developed with China and India, allowing the exchange of ideas and influence, and eventually a significant Muslim community. Unlike its East Asian and some of its Southeast Asian neighbours, the Philippines only became united as a cultural geopolitical entity in the 1500s, after Spanish conquistadors united most of the islands under their colonial control, naming the region after King Philip II (CHUA “Alternative Epistemologies” 115). As they did elsewhere in the empire, the Spanish actively spread Roman Catholicism which today is the most prominent religion in the Philippines. As with the practice of Catholicism in many Latin American Spanish colonies, Filipinos developed a syncretic approach to the faith, allowing many Indigenous values, beliefs, and ideas regarding mythology (MANANSALA 10) — important to Trese where the existence of the supernatural is both hidden and everyday (CHUA “Enabling Mythologies” 23; CHUA “Alternative Epistemologies” 112; MANANSALA 3) — to persist well throughout the three centuries of Spanish rule. As Filipino nationalism grew during the 19th century, a revolt against Spanish rule led to the departure of one colonial overlord for another in the form of the United States. Despite Philippine resistance, American forces occupied the Philippines after defeating the Spanish in the Spanish-American War in 1898. For the next 50 years, despite Filipino attempts to declare independence and a brief occupation by the Japanese during the Second World War, the US occupation had a dominating influence on the island, leading to the popular summation of Filipino “300 years in a convent, 50 in Hollywood” (Patrick FLORES et al.).

The modern tradition of Filipino komiks — so named as a Filipino translation with the tagalog hard K — largely arose during the period of US occupation, as the development of the American comics industry influenced that of the Philippines (Emil FLORES 75). The first known Filipino comic strip was Tony Velasquez’s still-running Mga Kabalbalan ni Kenkoy, first published in 1928 (DE VERA and ARONG 107). The deployment of US troops, in the build-up to World War Two, led to the popularization of the comic book format that soon was also adopted by Filipino creators. Both the Americans and the Japanese used komiks for propaganda purposes during the Second World War (Warren 15-16), but after the war ended and the Philippines were finally able to fully gain their independence, the stage was set for the “Golden Age” of komiks (DE VERA and ARONG 107).

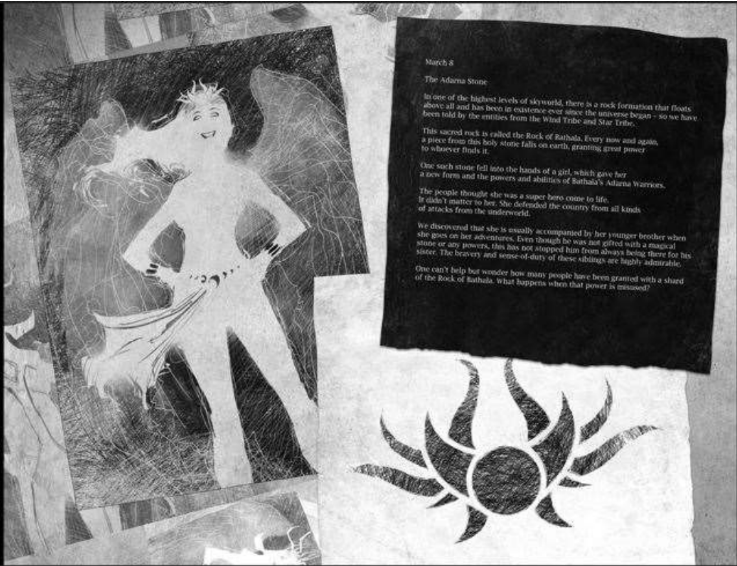

In conjunction with their hard-fought independence (Manila Treaty), Filipino artists and writers embraced the opportunity to tell their own stories and Filipino audiences lapped up the series. Initially, many were still rooted in American influences but redressed in the colours of Filipino nationalism. An iconic example of this would be the country’s first comic superheroine Varga — later renamed Darna — who showed more than a passing resemblance to DC’s Wonder Woman with clear influences from Superman and Captain Marvel.

Nevertheless, the incorporation of Filipino mythology—such as iconography from the flag and the rooting of Darna’s power in a magical white stone—helped popularize these komiks with Filipino audiences and make Darna one of the longest-running and most influential series ever published in the Philippines (FLORES E 76).

She still remains little known outside of the Filipino community, and critiques of her derivative origins have undermined her ability — and those of Golden Age Komiks in general — to move beyond their domestic market. Nevertheless, her powerful influence on Trese and other more recent Filipino komiks cannot be denied. In fact, during one of later episodes of Trese Vol. 1: Murder on Balete Drive, the mystery antagonist is revealed to be the young boy Ding who uses a powerful “Adarna” stone to become a powerful superhero in order to protect his sister, thus working the Darna mythology (Loc 118) — albeit unofficially — into the Trese universe (Loc 121). Tan and Baldisimo even dedicate this story to Darna’s creators Mars Revelo and Nestor Redondo (Loc 120).

Throughout this period, Filipino komiks often engaged with current events and popular celebrities, but by the 1980s the mainstream komiks publishing industry faced significant headwinds as fan interests, economic troubles, declining production quality, and new foreign technologies began to take effect:

Filipinos became more interested in romantic stories, but komiks mainly focused on graphically horrific tales and political satire. Second, Filipinos lost interest in serialised novels because they had less money to spend on forms that sometimes took years to finish, so the shorter stories were more popular because they came out cheaper. Third, the deterioration of the quality of komiks. Because artists were being paid per page, they were forced to take on as many jobs as they could; this resulted in artists spending shorter hours working on their craft, thus compromising quality. The drop in the quality was exacerbated by publishers who called for more and more works to be sold without much copy-editing. And lastly, globalisation introduced Filipinos to better technology in the form of television and the Internet. (DE VERA and ARONG 108)

The inability of komiks publishers to keep pace with changing consumer tastes, limited budgets, and the cheapening of production values, undermined the ability of the industry to react to the increasing competition from globalized foreign material, particularly from the US and Japan. Over time, many publishers closed down, but the tradition of comic creation still persisted, particularly as artists and writers moved to the independent space where they enjoyed more expressive freedom (VERA and ARONG 120). The stage was set for Trese to emerge.

Trese’s creators, Tan and Baldisimo, came out of this independent komiks tradition that continued to produce long after the golden age of Filipino mainstream publishing. Eventually the community grew strong enough to publish collectively-produced anthologies like the Bayan Knights that featured Filipino superheroes (FLORES E 77). Indeed, the love for the medium itself as both a mechanism for entertainment and expression remained established as a quintessential element of the cultural landscape. In his introduction to the first English-translated collected graphic novel Trese Vol. 1: Murder on Balete Drive, Gerry Alanguilan explains “The Philippines is a country that loves comics. The Filipinos love to read them, and love to create them. It’s an indelible part of Filipino history and culture” (Loc 5-6). The country itself has been known to export many talented illustrators to the United States. In the case of the American comics industry, efforts were made to increase Filipino representation in their comics, such as Wetworks’ Grail or Marvel’s all-Filipino Triumph Division superhero team. The latter team drew criticism from many Filipino fans, because certain characters — such as Great Mongoose or St. George both of which debuted as members of Triumph Division in 2008 — seemed to be based on animals not native to the country or saints not important in Roman Catholicism (FLORES E 75). Accused of not properly researching Filipino culture and geography, Triumph Division co-creator Matt Fraction dismissed these concerns, arguing that “absolute cultural accuracy” had to be abandoned for “ease-of-reading” and that he was writing for “Americans, not Filipinos” (FLORES E 77). As this instance demonstrates, while foreign comics traditions could occasionally feature Filipino representation, it was often at odds with their own cultural values, and could not be reliably counted on for telling authentic Filipino stories, a void indie komiks sought to fill.

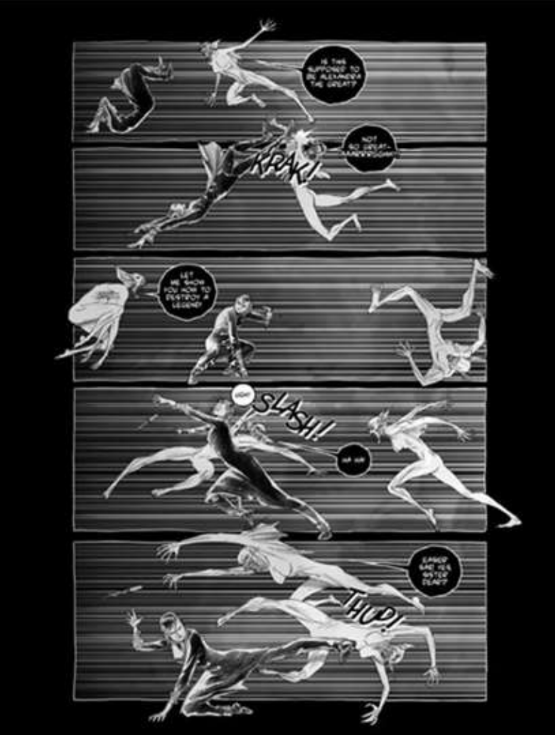

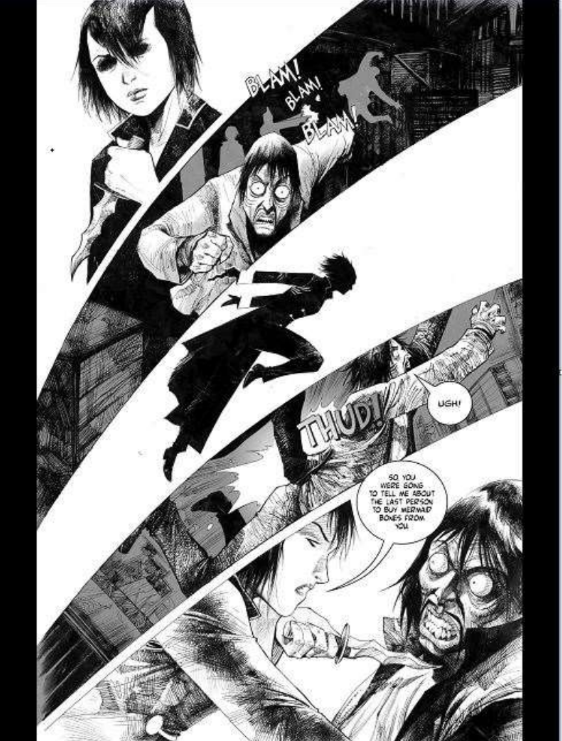

In keeping with its tradition, Filipino komiks, while focused on issues related to their domestic readership, absorbed outside factors especially American comics and Japanese manga (FONDEVILLA 441). Indeed, while komiks never truly developed a uniquely Filipino art style, they were able to adapt elements from foreign styles to tell their stories in their own way (VERA and ARONG). In the art style of Trese for example, echoes of conventional elements of Japanese manga abound, such as the frequent use of background speed lines (Trese Vol. 2: Unreported Murders Loc 13; Trese Vol. 4: Last Seen After Midnight Loc 9; Trese Vol. 6: High Tide at Midnight Loc 43-44), the occasional chibi-like depiction of the characters (Trese Vol. 4: Last Seen After Midnight Loc 67), and the emphasis on clean black and white panelling and page design — particularly in the earlier volumes (MANANSALA 25) — with many of the illustrated depictions of local gods and entities reminiscent of Japanese shingami (death god) manga (CHUA “Enabling Mythologies” 22).

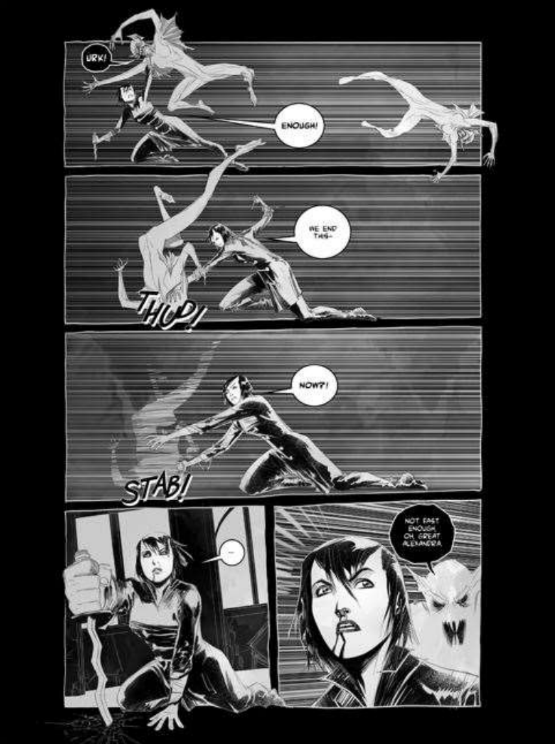

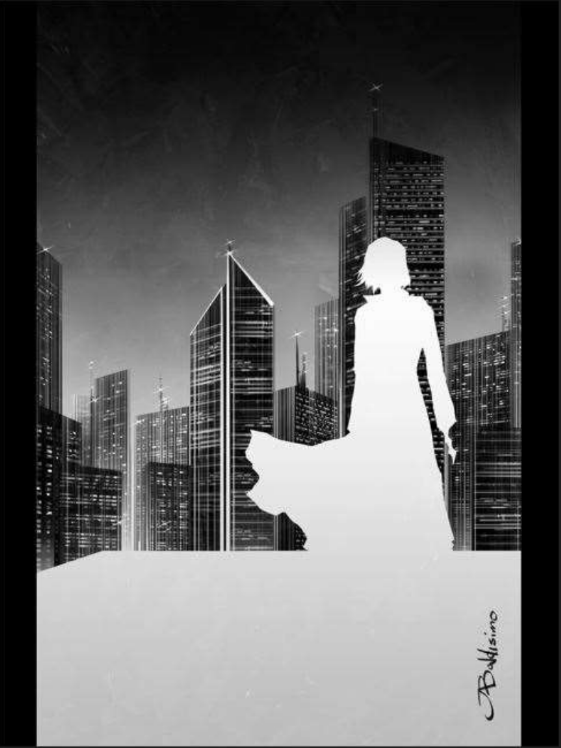

While some might be tempted to misread Trese as a manga, there are some key differences that distinguish it from most commonly seen depictions of the Japanese version of comics. For one, although the title character is a young woman, in the komiks at least there are no big emotive eyes with elaborate lashes. In fact, Trese’s eyes are rarely seen at all, often hidden behind her bangs which in the komiks are often angled to give her forehead the outline of devil’s horns. While this was changed for the Netflix series which gave her far more anime-esque eyes and less diabolical bangs, Trese’s appearance in the comics remains far from “kawaii” with the character rarely if ever breaking her stern, unemotional demeanour. Indeed, the komiks version of Trese often depicts conventionally masculine qualities, perhaps reflecting Tan and Baldisimo’s original intention to cast a male character Anton as their lead supernatural detective — albeit one rooted in mysticism over Sherlock Holmes-like rationalism (CHUA “Alternative Epistemologies” 106) — before opting to make him Trese’s father instead. Even in the komiks itself, Trese often has to declare “I am nothing like my father,” usually the context being she is far less forgiving and even more potentially dangerous than he was (Trese Vol. 1: Murder on Balete Drive Loc 27).

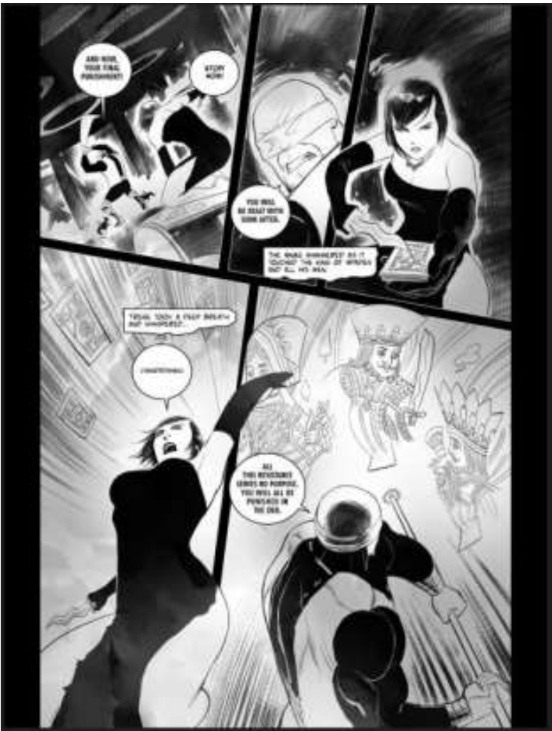

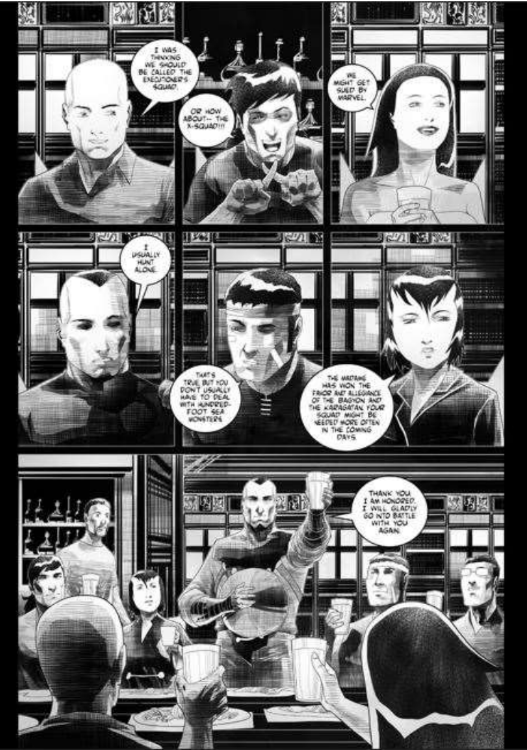

The serious characterization of Trese herself, always cool even in the face of danger (Trese Vol. 1: Murder on Balete Drive Loc 23), evokes many of the noir genre protagonists from US and British comics and popular culture that undoubtedly influenced Tan and Baldisimo in their design of Alexandra Trese. Her ability to confront and intimidate powerful supernatural enemies that she defeats and outsmarts mostly through her own wits — and the frequent use of reluctant allies — is reminiscent of the British blue-collar warlock and occult detective John Constantine from DC comics (CHUA “Enabling Mythologies” 21). Tan and Baldisimo are not shy about their fandom of American comics with multiple allusions to both DC and Marvel peppered throughout the series, including an homage to Superman’s debut cover Action Comics #1 (Trese Vol. 5: Midnight Tribunal Loc 62). References are made to legends like Neil Gaiman (TAN and BALDISIMO Trese Vol. 3: Mass Murders Loc 5) and Alan Moore (TAN and BALDISIMO Trese Vol. 2: Unreported Murders Loc 75). In Trese Vol. 6: High Tide at Midnight, one of Trese’s allies jokes that “we might get sued by Marvel” after the group forms an Avengers-like team (Loc 155).

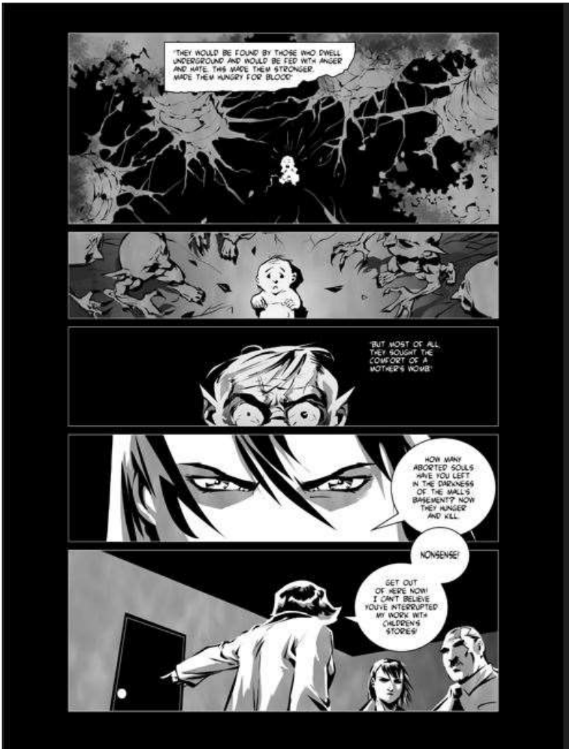

Yet, despite some Western elements in Trese’s characterization, she is far from a typical Hollywood heroine. A heroic protector of Manila with significant anti-heroic qualities and deep immersion in the realities of everyday life (MANANSALA 1; TAN and BALDISIMO Trese Vol. 1: Murder on Balete Drive Loc 94), Trese is not only willing to use brutality or even kill to protect her city should the need arise (TAN and BALDISIMO Loc Trese Vol. 1: Murder on Balete Drive 25), she is willing to tolerate the continued existence of corrupt politicians, organized criminal gangs, and violent monsters so long as they respect the balanced status quo (TAN and BALDISIMO Loc Trese Vol. 1: Murder on Balete Drive 27). Like an archetypical chosen one, Trese is prophesized to either bring about a great age of darkness for the supernatural underworld, or seal it and all magic off from humanity for good (TAN and BALDISIMO Loc Trese Vol. 3: Mass Murders 94). As a character, however, she seems largely disinterested in either outcome and continues to chart her own path somewhere in the middle (CHUA “Enabling Mythologies” 26). Furthermore, she is a character imbued with the values of her Filipino culture, which can at times be at odds with those of foreign audiences. For example, while Trese stories generally follow a monster-of-the-week format, the monster antagonist in question is sometimes human. In one notable case — “Embrace of the Unwanted” in Trese Vol. 2: Unreported Murders — Trese discovers a group of murderous tiyanak in a mall parkade that have been attacking and killing evening patrons (Loc 86). According to Tan and Baldisimo, the tiyanak are demonic babies that sometimes are the souls of aborted fetuses. Sure enough, Trese discovers an abortion clinic operating above the parkade and confronts the female doctor in charge, who defends her actions as helping women who have been sexually assaulted (Loc 91-92).

Trese makes it clear that the titular heroine, and by extension her authors, still consider these actions to be murder. The fate of the doctor being killed at the end of the story by one of the tiyanak left behind (Loc 93) — a similar ironic justice given to many other murderous villains in the series — underpins the creators’ conservative Roman Catholic values on this particularly divisive issue. The villainization of the doctor also echoes an undercurrent of anti-rationalism as Trese often confronts scientifically-minded skeptics, such as with Dr. Tuason in Tan and Baldisimo’s Vol. 4: Last Seen After Midnight (CHUA “Alternative Epistemologies” 107), who attempt to dispute the supernatural only to be forced to reckon with it.

Unlike many female protagonists in comics from Western countries, especially those written by men, Trese has — at the time of writing — yet to encounter a true love interest. While she ostensibly runs a popular nightclub called the Diabolical as her “day job”, she never exhibits any romantic desire for any patrons and is quick to shut down an “engkandata” — a beautiful tall elf-life forest shapeshifter known for seducing and enslaving men — working her charms on the premises (TAN and BALDISIMO Trese Vol. 4: Last Seen After Midnight Loc 14, 36). There are some characters who, perhaps against better judgment, do attempt to court Trese. Most notably Maliksi, a member of the tikbalang — an anthropomorphic horse-like species who can take human form and are obsessed with and known for their speed (TAN and BALDISIMO Trese Vol. 1: Murder on Balete Drive Loc 64). He served as the main antagonist in one of the Trese Vol. 1: Murder on Balete Drive cases only to evolve first into a vigilante and then ally of Trese, although she so far has characteristically ignored his flirtations (TAN and BALDISIMO Trese Vol. 5: Midnight Tribunal Loc 130). Furthermore, Trese lacks both the voluptuous physique of femme fatale or the hyper-musculature of a typical superheroine from Western comics. Instead, she simply looks like an average physically fit Filipino woman, and her characterization is all the stronger for it. She is typically depicted wearing a long-fitting modern cut but traditionally-inspired trench coat, and wields a wavy-bladed traditional Filipino gunong (dagger) as her trademark weapon. It is later revealed that this dagger contains the pure soul of her twin sister who died soon after birth (TAN and BALDISIMO Trese Vol. 3: Mass Murders Loc 92). While she has five older brothers — some of whom do appear in later volumes — they are mostly absent, off fighting a war in the underworld while Trese stays behind to defend “her city”. As Ana Micaela Chua notes in “Enabling Mythologies: Specificity and Myth-Making in Trese”, Trese’s decision to stay represents a form of everyday heroism in a country known for its vast levels of emigration:

It may sound kitschy, but the notion that it is one’s duty to stay in the country is significant in a country that loses about 10% of its population to migration. Alexandra’s special training puts her at the same level as professionals for whom the temptation to leave, to make it in the global market, is strong primarily because compensation is better. Alexandra may choose to join her brothers - to bring the war to the underworld - yet she chooses to work case by case at the margins of the battle against evil, to address the needs of those for whom that battle is not some grand epic, but the comedy of the everyday.

As such, while her brothers might be taking their fight through a literal hell, Trese eschews that glory to defend the everyday people in the here and now, a valiant figure to those who choose to stay in spite of greater opportunities elsewhere.

While Tan and Baldisimo acknowledge the shadow of Western and other foreign influences on their work, the infusion and prominence of Filipino elements, such as the myriad of creatures from Filipino mythology and the references to recent events in the country, keep Trese far from feeling overly derivative. Indeed, both Japanese manga and American comics have always taken in outside influence as well as exporting their own. Osamu Tezuka, the “grandfather of manga”, famously modelled the head design of his most iconic character Tetsuwan-Atomu, or Astro Boy, after that of Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse (MISAKA 25). Marvel and DC — the United States’ historically most prominent comics publishers — have also long explored applying manga elements to their characters, such as with the Bat-manga! (KUWATA) or Marvel Mangaverse. Indeed, understanding that no regional comics tradition is truly acting in full isolation, it stands to reason that Filipino komiks creators like Tan and Baldisimo can adapt these foreign influences to tell their own stories (JAVIER 87). As Carljoe Javier explains in “Filipino Humour and the Filipinisation of Foreign Tropes in Macoy’s Taal Volcano Monster vs. Evil Space Paru-Paro”, Filipino creators are adept at creating works that utilize foreign ideas while maintaining their own “pinoy” spin, the result being something that “…is not Japanese, though it is influenced by the Japanese. It is not American, though it is influenced by the Americans. It is not Spanish, though it is influenced by the Spanish” (Javier 92). In recognizing and using their diversity of foreign cultural influences — not to mention that vast diversity of Indigenous cultures on the islands themselves — Filipino komiks creators can both speak to their own cultural experience authentically while also remaining accessible to global audiences (CHUA “Enabling Mythologies” 24).

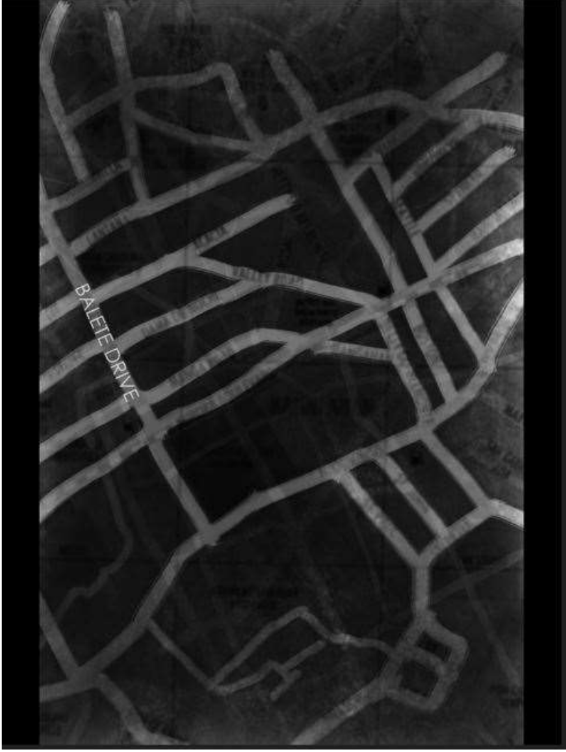

Thus, while the Trese komiks certainly remain accessible to foreign readers — as a long as a translated version is available — the series is rooted in its Filipino origins as part of its creative agenda. Tan has published multiple books on Filipino mythology and he and Baldisimo embed it into story alongside maps of city neighbourhoods like Balette Drive (Trese Vol. 1: Murder on Balete Drive Loc 9).

Many creatures both obscure and more widely known enjoy a starring role in Trese — and often with an urban fantasy update — as they emerge as friend or foe to the series’ protagonist. In Trese’s Manila, creatures as diverse as the vampiric aswang and bagyon storm gods — here re-imagined as smuggling gangs and power company executives respectively (MANANSALA 21) — all must play by the rules or expect a visit from Trese and her loyal mask-wearing twin children-of-a-war-god enforcers, the Kambal.

While not all creatures depicted are solely found in the Philippines — the spectral white lady from the first case coincidentally bears more than a passing resemblance to the first episode of the long-running American also-monster-of-the-week television series Supernatural (KRIPKE) — Trese’s creators always reimagine them in a Filipino context. In the words of Ana Michaela Chua:

TRESE exposes Metro Manila as a shared world: it is shared not only by human inhabitants, but also by the paranormal beings that have, for so long, already been part of Philippine culture. It is not just typical, everyday, mainstream Metro Manila, but also Metro Manila of the marginalized, its street corners and crannies, its unwanted citizens and its dead. (“Alternative Epistemologies” 115)

As such, Tan and Baldisimo’s Manila is a city at once human and non-human, modern and traditional, both open to — and wary of — the forces beyond its national borders, both natural and supernatural (CHUA “Alternative Epistemologies” 103).

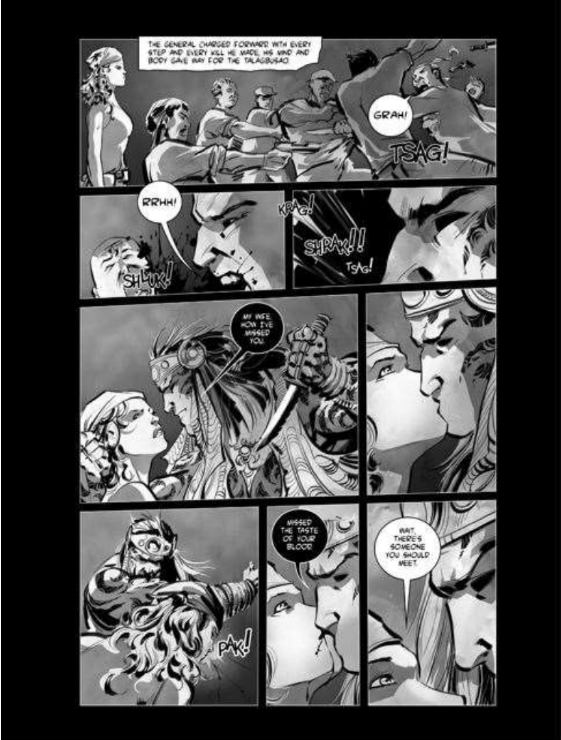

While Trese’s depiction of Filipino mythology is largely appreciated in its home country, some concerns have been raised, particularly about the characterization of Talagbusao — the father of the Kambal (Trese Vol. 3: Mass Murders Loc 62).

Serving as Trese’s most fearsome antagonist in both the earlier volumes of the komiks and the Netflix series, the Talagbusao appears in traditional Indigenous dress and displays an obsession with bloodthirsty ultra violence and human sacrifice. Anthropologists Andrea Malaya M Ragragio and Myfel D Paluga took issue with this conceptualization of the deity, arguing that the hyper-violent chaotic villain seen in the Netflix series and the komiks had more in common with Western misinterpretations by American anthropologist Fay-Cooper Cole from the early 1900s than they did with actual Indigenous belief-systems. “The Talagbusao depicted in Trese barely resembled what Indigenous communities in Mindanao mean when they talk about this entity or its related forms, called busaw” (RAGRAGIO and PALUGA). Rather than a spirit of mad chaos and violence, the Talagbusao is actually a more nuanced figure, mostly associated with power and potency. Far less well-known than other entities from Filipino mythology such as the aswang or the earth spirit duwende, the Talagbusao also hails from Indigenous communities on the island of Mindanao. This southernmost major island in the Philippines has significant cultural, religious, and historically political separation from Manila, and has often been the primary site of civil war in the country. As such the depiction of the Talagbusao — while useful in giving Trese a powerful domestic adversary that cannot easily be defeated — conveys some problematic elements, particularly when taken in the context of the marginalization of Mindanao and Indigenous cultures within the Philippines.

Nevertheless, Tan and Baldisimo have tried to address some of the domestic criticisms levelled against their works. Set in the country’s most (in)famous chaotic urban sprawl, the series has sometimes been accused of being Manila-centric, with many of the mythological creatures abandoning their traditional homes to seek new opportunities in the giant dangerous city, much like many Filipino migrants from rural areas (CHUA “Enabling Mythologies” 23).

As the volumes progress, Tan and Baldisimo retain the urban setting so critical to the plot, but they world-build with more references to other parts of the country, including references to the ongoing civil war in the south where both sides are shown to be capable of brutality (Trese Vol. 3: Mass Murders Loc 40). As Trese works closely with the police — in particular Captain Guerrero, who calls her in whenever a case takes a supernatural turn — the series received criticism that the reality of police corruption in the Philippines was not being adequately depicted. In response, Tan and Baldisimo created the “The Outpost on Kalayaan Street” in which an inmate raises the dead in a graveyard slum to take revenge on the police officer who killed his brother (TAN and BALDISIMO Trese Vol. 2: Unreported Murders Loc 58). While the neighbourhood police in this story are largely depicted as violent and corrupt, the story itself is still broadly seen from a police perspective (MANANSALA 6). Nevertheless, many of the residents refuse the police’s order to evacuate as they assume it is just a ruse to get them out so their camp can be demolished (TAN and BALDISIMO Trese Vol. 2: Unreported Murders Loc 44). Likewise, many of the police shown stealing booze and threatening to beat prisoners, although Guerrero and the targeted officer are shown in a more positive light (TAN and BALDISIMO Trese Vol. 2: Unreported Murders Loc 48).

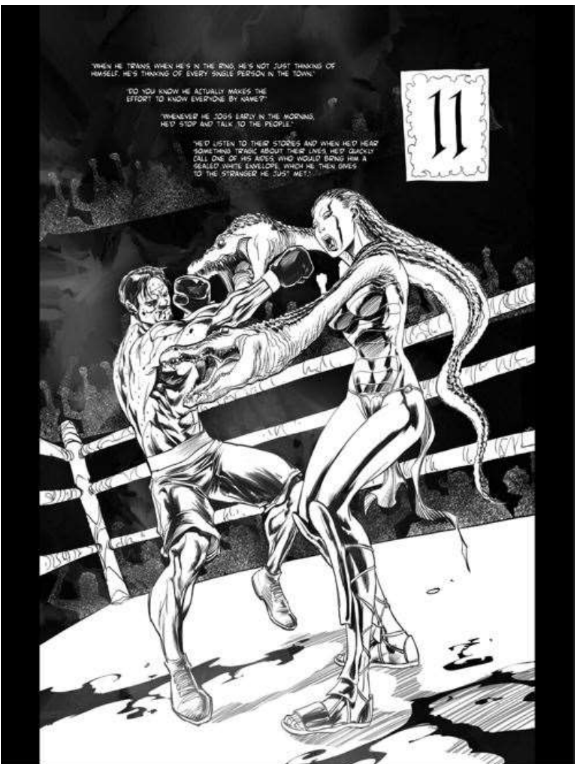

Tan and Baldisimo also reinforce Trese’s connection with current Filipino culture by referencing major domestic cultural phenomena, both positive and negative. In “The Fight of the Year” from Trese Vol. 4: Last Seen After Midnight, Trese interacts with “Manny”, a legendary Filipino boxer who fights each year in a secret underground match where he must defeat twelve supernatural opponents in twelve rounds in order to ensure that his city of General Santos is protected for another 12 months (TAN and BALDISIMO Loc 117).

This character is a clear reference to Manny Pacquiao, the legendary Filipino boxing champion turned politician who ultimately lost his bid for the presidency in 2022 (“Halalan 2022”). In Tan and Baldisimo’s depiction, Manny is presented as an equal to Trese and one of the few willing to stand up to her. He is seen as a heroic figure who made a deal with a devil to become a famous boxer only to become a selfless defender of his community. Chua notes that this “Sytan” figure is rooted in popular conceptions of Pacquiao’s infamous boxing manager, complete with potentially problematic cultural beliefs surrounding Filipinos of Chinese descent:

At once Satan and a Fil-Chinese mogul, this devil is based on Pacquiao’s notorious patron, Chavit Singson. Sytan thus combines the stereotypical bias against rich Chinese and the general public dislike of Singson, whose association with gambling, corrupt politics, self-confessed cruelty, and indelicacy in front of the media have rendered him particularly demonic to the public. (“Enabling Mythologies” 27)

Tan and Baldisimo thus glorify one Filipino figure while literally demonizing another. The tension towards the Chinese community is not only driven by the accumulation of wealth in the hands of a few Chinese-Filipino business owners, but also exacerbated by ongoing tensions with China, particularly over the South China Sea where China has been trying to enforce its claim over territorial waters practically up to the Philippine coastline (SIMONETTE and GUINTO). Singson also represents another example of a corrupt and cruel elite whose misdeeds raise the question of whether he will ever truly see justice, and certainly the Sytan character continues to profit off of Manny even at the close of this story in Trese.

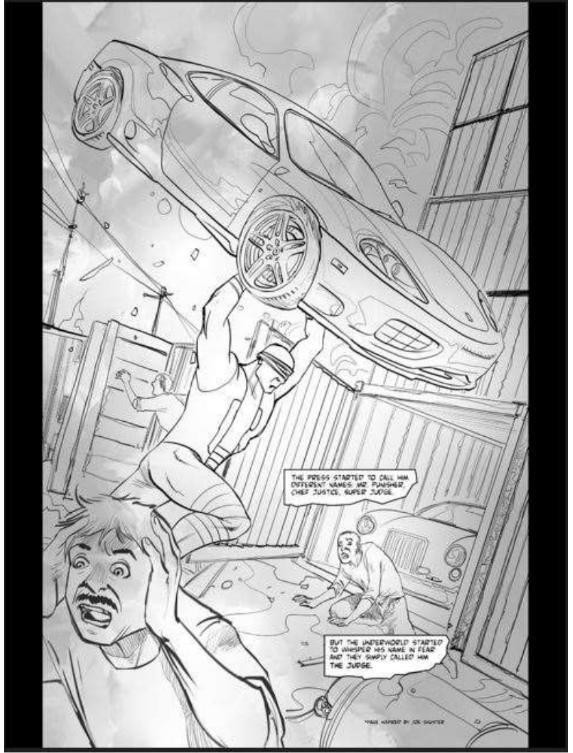

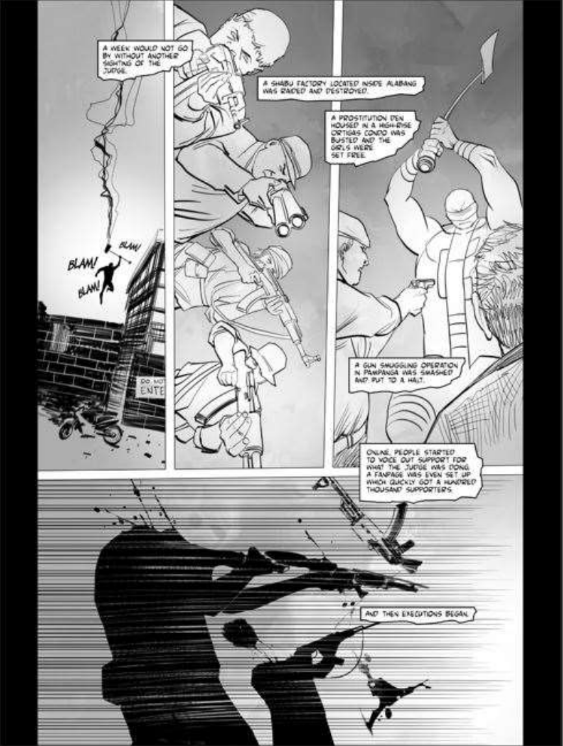

In Trese Vol. 5: Midnight Tribunal, Tan and Baldisimo introduce the judges, super-powered justice enforcers with lethal vigilantism who target criminals that the law cannot reach. While their methods are brutal, the judges remain popular with a local populace tired of traditional law enforcement’s inability to deal with the problem (Trese Vol. 5: Midnight Tribunal Loc 63). The judges are quite reminiscent of the appearance of vigilante death squads—under recent president Rodrigo Duterte’s administration—that sought out and summarily executed those perceived as criminals without a proper trial. While their actions were abhorrent to foreign observers, these squads—like the judges—were often quite popular with local communities who had lost faith in the Filipino justice system.

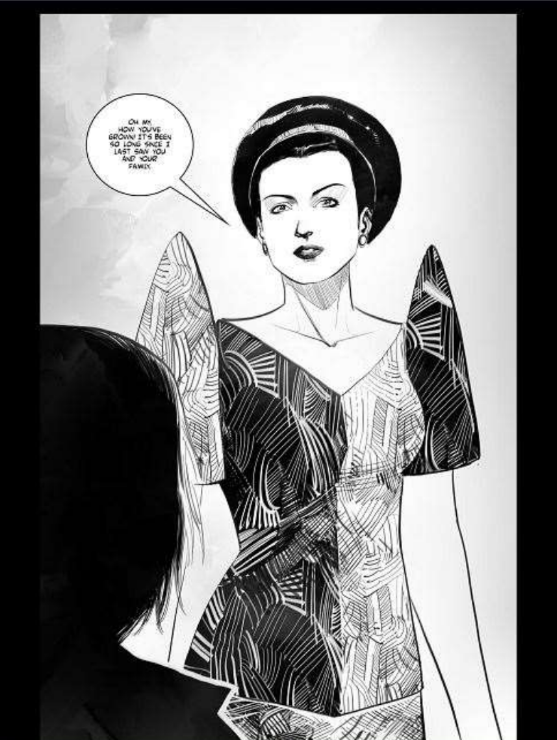

As they moved to work more prominent Filipino elements into their komiks, Tan and Baldisimo settled on a newly returned political figure to be a major new enemy for Trese. While Tan and Baldisimo never address the issues surrounding their characterization of the Talagbusao, in later volumes they do pivot away from using him as Trese’s arch enemy. Instead, they positioned Trese’s new nemesis as “the Madame” — a powerful political figure modelled after notorious former First Lady Imelda Romualdez Marcos (Trese Vol. 5: Midnight Tribunal Loc 93), wife of former Filipino dictator Ferdinand Marcos and mother of recently elected president Bongbong Marcos. A corrupt figure known for her obsession with high fashion and charming foreign powers, the First Lady and her husband stole billions from the national coffers to finance their lavish lifestyle before being ousted in 1986 (DE GUZMAN). Despite public outrage and anger towards her and her family, Imelda Marcos was able to massage their image enough for her son to be elected as president, undermining the government’s attempts to seek justice for her past crimes. As a master manipulator with a sweet smile and Machiavellian ruthlessness, the Madame could certainly serve as a major foil for Trese, although her characterization could incur the ire of the current Marcos’ administration.

By emphasizing these contemporary political figures and domestic everyday realities such as shantytowns, rebel outposts, power outages, and wealthy uncaring corrupt politicians, Trese emphasizes its status as a tale produced in a developing country, with considerably less wealth and political stability than found in Japan or the West. By connecting with the issues in their home country — and the critiques from their readers — Tan and Baldisimo are able to infuse their fantasy narrative with an authentic dose of realism that reinforces its connection to Philippine culture while also situating it within the context of the wider world (CHUA “Enabling Mythologies” 22). In addition to their embrace of traditional mythological figures and beliefs, they also incorporate modern urban legends — such as that of a lizard man living under the mall and preying on young women (TAN and BALDISIMO Trese Vol. 2: Unreported Murders Loc 75) — and traditional practices infused with modern symbology, such as Trese’s use of the logo on a thrown away pharmacy bag as a sigil for a healing spell (TAN and BALDISIMO Trese Vol. 3: Mass Murders Loc 131).

In doing so they create a compelling narrative that is both realistic and fantastic, traditional and modern, foreign and Filipino.

These dichotomies have enabled Trese to gain a foothold amongst global audiences while also remaining impactful for its domestic readers. While Tan and Baldisimo’s series still has its critics and some foreign-influenced biases in a country that is still trying to find its identity after decades of tumultuous independence, it represents a valiant effort in broadening understanding of Philippine mythology, culture, and creativity within a global context. As Chua notes:

Much of TRESE is about coming to terms with internal differences without losing sight of the communal nature of cultural experience. Through its twin trajectories of the universal and the local, of the mythical and the real, the historical and the contemporary, TRESE reflects Philippine society’s struggle to locate itself in the context of the larger world, as well as its desire for self-definition against the rest of that world. (Enabling Mythologies 29)

In many ways, the Philippine komiks experience speaks to that of many under-represented comics traditions that use the sequential art medium to explore their cultural identity and represent it both narratively and artistically. Using both their love of foreign influences and domestic source material, Tan and Baldisimo’s work will hopefully open the door, not only to more adaptations of Trese, but other Filipino writers and illustrators to receive the global and local audiences — and scholarly attention — which they deserve.

Bibliographie

CAYTON, Ria. “Myths, Komiks, and the Demand for Filipino Stories”. International Conference on Philippine Studies (ICOPhil), 2016, Dumaguete. Qtd in CRC Staff. “Myths, Komiks, and the Demand for Filipino Stories: Research Notes and Insights from UA&P Literature Instructor Ria Cayton”. Center for Research and Communication. 26 July 2019. https://crc.uap.asia/2019/07/26/myths-komiks-and-the-demand-for-filipino-stories-research-notes-and-insights-from-uap-literature-instructor-ria-cayton/ Accessed 3 July 2024.

CHUA, Ana Micaela. “Alternative Epistemologies in Budjette Tan and Kajo Baldisimo’s Trese.” Vol. 13, no. 2, 2016, pp. 102–126.

--. “Enabling Mythologies: Specificity and Myth-Making in Trese”, in Cultural Excavation and Formal Expression in the Graphic Novel, edited by Jonathan C Evans, Inter-Disciplinary Press, 2013, pp. 21–31.

DE GUZMAN, Chad. “How Cultural Fascination With Imelda Marcos Has Obscured Her True Legacy”, Time, 27 July 2023, https://time.com/6298212/here-lies-love-imelda-marcos-legacy/. Accessed 6 Oct 2023.

DE VERA, Denise Angela, and Marie Rose ARONG. “Cracking the Filipino Sequence: Two Factors That Shaped Contemporary Philippine Komiks.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, vol. 10, no. 1, 2019, pp. 106–121.

FLORES, Emil Frances M. “Up in the Sky, Feet on the Ground: Cultural Identity in Filipino Superhero Komiks”, in Cultural Excavation and Formal Expression in the Graphic Novel, Inter-Disciplinary Press, 2013, pp. 75–86.

FLORES, Patrick, et al. 300 Years in a Convent, 50 in Hollywood: In Celebration of Filipino American History Month. October 6, 2021. Effron Center for the Study of America, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ.

FONDEVILLA, Herbeth L. “Contemplating the Identity of Manga in the Philippines.” International Journal of Comic Art, Vol. 9 Iss. 2 (2007): pp 441–53.

“Halalan 2022”. ABS CBN News, 13 May 2022, https://halalanresults.abs-cbn.com/ Accessed 15 December 2023.

ICHIMURA, Anri. “Trese Lands in Netflix's Top 10 TV Show Rankings in 19 Countries,” Esquire, 14 June 2021. https://www.esquiremag.ph/culture/movies-and-tv/trese-international-rankings-a00304-20210614. Accessed 15 Sept 2023.

JAVIER, Carljoe. “Filipino Humour and the Filipinisation of Foreign Tropes in Macoy’s Taal Volcano Monster vs. Evil Space Paru-Paro”, in Cultural Excavation and Formal Expression in the Graphic Novel, Inter-Disciplinary Press, 2013, pp. 87–93.

KRIPKE, Eric. "Pilot." Supernatural, directed by David Nutter Reich, The WB, 2005.

KUWATA, Jiro. Batman: The Jiro Kuwata Batmanga. Vol. 1. DC Comics 2014.

MANANSALA, Ana Micaela CHUA. “Communal Homes and Heterotopic Contagion in Trese.” Between, Vol. 8, no. 15, 2018. https://doi.org/10.13125/2039-6597/3235 X. Accessed 15 December 2023.

MANILA TREATY. United States, Republic of the Philippines. Treaty of General Relations and Protocol. Library of Congress, https://maint.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/b-ph-ust000011-0003.pdf. Treaty between the United States and the Philippines.

Marvel Mangaverse. Marvel Comics, 2000-2002.

MISAKA, Kaoru. “The First Japanese Manga Magazine in the United States.” Publishing Research Quarterly. Winter 2004, Vol. 19 Issue 4, pp. 23-30.

RAGRAGIO, Andrea Malaya M, and Myfel D PALUGA. “What Netflix Got Wrong About Indigenous Storytelling”, Sapiens: Anthropology Magazine, 1 Dec 2021, https://www.sapiens.org/culture/busaw-trese/. Accessed 15 Sept 2023.

SIMONETTE, Virma, and Joel GUINTO. “BBC Witnesses Chinese Ships Blocking Philippines Supply Boats”, BBC, 6 October 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-67015857. Accessed 6 Oct 2023.

TAN, Budjette, and Kajo BALDISIMO. Trese Vol. 1: Murder on Balete Drive. E-book ed., Ablaze, 2020. Graphic novel.

--. Trese Vol. 2: Unreported Murders. E-book ed., Ablaze, 2021. Graphic novel.

--. Trese Vol. 3: Mass Murders. E-book ed., Ablaze, 2021. Graphic novel.

--. Trese Vol. 4: Last Seen After Midnight. E-book ed., Ablaze, 2022. Graphic novel.

--. Trese Vol. 5: Midnight Tribunal. E-book ed., Ablaze, 2022. Graphic novel.

--. Trese Vol. 6: High Tide at Midnight. E-book ed., Ablaze, 2023. Graphic novel.

WARREN, Bernard, ed. Cartoons for Victory. Fantagraphic Books, 2015.

WheNetflix. “Trese Season 2: Premiere Date, Schedule, Spoilers and Rumors,” WheNetflix, 15 September 2023. https://whenetflix.com/trese. Accessed 15 Sept 2023.