Cut My Life Into Pieces: Alzheimer’s, Identity, and the Closure of Selfhood in Sarah Leavitt’s Tangles: A Story of Alzheimer's, My Mother, And Me

Table

Abstract

Francese | IngleseLes troubles neurodégénératifs tels que la maladie d'Alzheimer et leurs effets sur le souvenir du monde qui entoure les malades remettent fondamentalement en question les conceptions habituelles de l'identité et de la mémoire, et la représentation littéraire permet de comprendre comment l'intersection de l'esprit, du corps et de l'environnement façonne l'identité. Les mémoires graphiques de Sarah Leavitt, Tangles : A story about Alzheimer's, My Mother, and Me, de Sarah Leavitt, utilise les techniques narratives uniques du support

graphique pour remettre en question une conception ancienne de l'identité humaine, à savoir que l'identité est entièrement le résultat d'un esprit qui fonctionne et qu'une archive mentale altérée efface l'identité d'une personne. Au contraire, le texte utilise l'histoire de la mère de Leavitt, Midge, pour affirmer que l'identité est relationnelle - elle se forme lorsque l'esprit et le corps suturent les informations mentales, physiques et environnementales en une vision du monde cohérente. De la même manière que la fonction de clôture d'une bande dessinée trouve son sens dans les espaces vides entre les cases, l'identité se forme à partir d'un ensemble d'informations que le processus de mise en intrigue aide à composer.

1. Introduction

When discussing neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease, the sheer degree to which the sufferer seems to slip away raises questions about whether or not their identity remains intact. Can they even claim to have an identity when the disease so thoroughly destroys their memory of even the most basic aspects of life? Literature is an avenue to approach these questions, and Sarah Leavitt’s graphic memoir, Tangles: A story about Alzheimer’s, My Mother, and I deftly interrogates the intersection of mind, body, environment, and identity through its graphic form. The text uses the story of Leavitt’s mother, Midge, to interrogate a longstanding conception of human identity: that selfhood is exclusively the result of a functioning mind, such that severe mental disruption causes the complete annihilation of the self. However, despite many panels pointing towards this same conclusion, Leavitt’s text simultaneously presents an alternate reading. This alternate model of identity asserts that instead of the brain being an archive of information that either functions or not, identity is a gestalt - it is formed from the ability to suture together mental, physical, environmental, and cultural information into a cohesive map of meaning. In the same way that the fragmentary information of a comic’s panels cohere in the blank spaces between them, our identity involves an active process of meaning-making, whereby the connotative meanings that surround us suture together through our own narrativity. By framing Alzheimer's as a condition which fractures this capacity to form signifying chains with the world around us, the text represents Midge with incredible sympathy. Rather than reducing her to an empty shell – a former person whose subjectivity has been outright deleted – Midge is someone whose grasp on the relationality of her own identity is impaired. Midge may not have the ability to draw closure with the world, but this deficiency does not mean she is absent.

2. The Mind/Body Divide

Questions about the exact structure of the human mind and its relationship with both personal identity and the surrounding world have prompted centuries of shifting debate and speculation from across the scientific and philosophical communities. For instance, several earlier theorists believed that the mental sphere was fundamentally separate from the material world. In his 1641 book Meditations, Rene Descartes “insisted that it is consciousness and the ability to know through reason and radical doubt that defines human beings and places them above the rest of the material world”. Descartes believed that the human intellect was categorically elevated above the body - that “the human mind was an indivisible thinking substance governed by entirely separate laws from those that rule the body” (EL REFAIE 60). In Descartes’ view, individual identity is wholly disconnected from the physical world.

Similarly, Enlightenment philosopher John Locke conceptualized a system where functioning mental energies define personhood. When he “develop[ed] the first systematic analysis of continuity of personhood over time in terms of psychological properties”, he proposed that “we are the same person over time when our consciousness extends back to past actions and thoughts” (HEERSMINK 2). This kind of continuity assumes the brain as a kind of “archive”: a storeroom of information which maintains personhood over time by accessing “specific and accurate memories of past actions and thoughts” (2). Perspectives like those of Descartes and Locke place the mind in a box which controls a body, but simultaneously lacks a presence in the body, so to speak. A person’s identity is somewhere else entirely.

However, there are wide-reaching consequences to divesting the mind from the body, especially when discussing dysfunctional or disabled minds. In fact, the archival model of personhood threatens to completely erase the identity of individuals whose minds have been altered or damaged by diseases or injuries. It is here that Alzheimer’s disease enters into the conversation. The way personhood is constructed necessarily impacts how Alzheimer’s patients are framed and treated. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, Alzheimer’s disease is a neurological disease that causes dementia, the “general term for memory loss and other cognitive abilities serious enough to interfere with daily life”. While the cause of the disease is largely unknown, it is understood that the progression of Alzheimer’s creates “[t]wo abnormal structures [in the brain] called plaques and tangles'', which “somehow play a critical role in blocking communication among nerve cells and [disrupting] processes that cells need to survive”. The impaired neural links and subsequent cell death cause an assortment of negative symptoms, which include “memory failure, personality changes, [and] problems carrying out daily activities''.

Because neuroscience has a poor understanding of the mechanisms of Alzheimer’s and the minds that it impacts, human culture has turned to the less scientifically rigorous framing devices of philosophy and art to bridge this gap. However, the chosen framework will not remain bound within the scientific community. Rather, it can expand outward and impact how Alzheimer’s patients are culturally perceived. For instance, the separation of mind and body into different spheres has resulted in a kind of hierarchical spatial metaphor. Frederic Jameson explains that when the human mind is positioned as the locus of individuality and identity – as the “autonomous bourgeois monad or ego”, in his words (JAMESON 23) – this monad becomes the center of the mind/body dualism. This aesthetic metaphor places the monad of identity deep within, and the physical flesh which wraps around it becomes an outer shell. Jameson calls this framework a “depth [model]” (12) which draws a positional and moral distinction between the ‘truthful’ core within and the ‘inauthentic’ coating without. Examples of depth models, which include “the dialectical one of essence and appearance” (12) or the “existential model of authenticity and inauthenticity” (12), all put forward a nigh-on moralistic divide between the body and the mind; our bodily experiences are so thoroughly cut off from the ‘true’ center of identity that the model construes our flesh as a matter of inauthentic appearance. The essence of our very humanity lies within, says the depth model.

The depth model is more than a simple matter of aesthetic representation – it has real consequences for real people. In fact, any model of subjectivity which hierarchically positions the mind over the body threatens to completely erase the Alzheimer’s patient. This is because disorders which degrade the brain, i.e. the location of our human essence, would therefore degrade personhood itself. In this sense, Alzheimer’s “has been culturally constructed around the metaphor of losing one’s mind, of ‘losing one’s selfhood’” (DALMASO 80). An Alzheimer’s patient is no longer a person because the thing that contained their personhood has been hollowed out. The destruction of neural function transforms an Alzheimer’s patient into nothing more than a shell unoccupied by their essence – a vacant body that once contained a person.

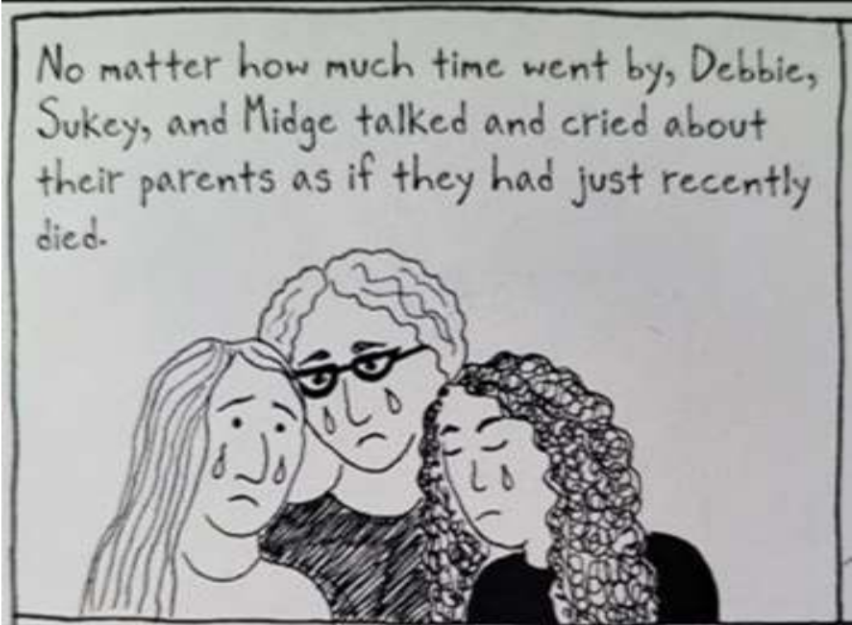

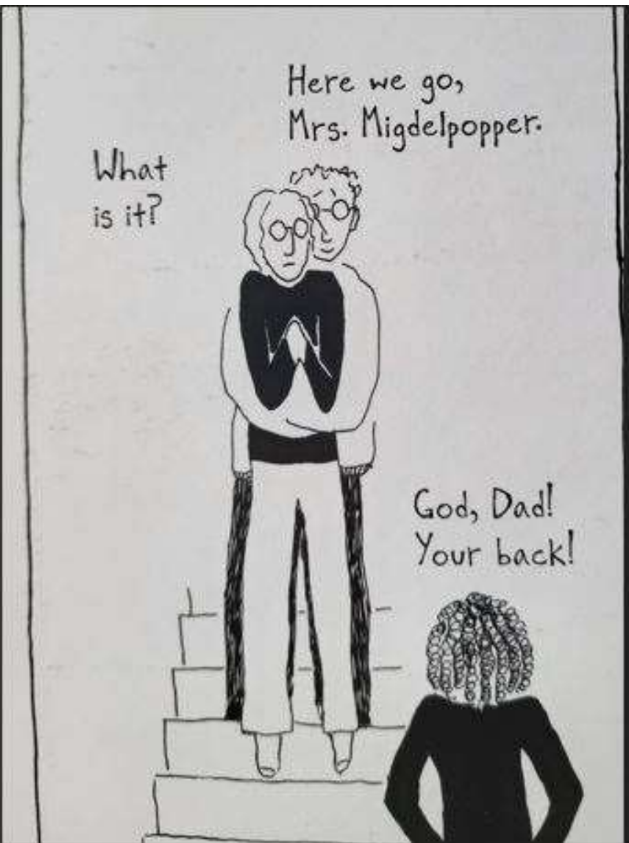

In Renata Lucena Dalmaso’s article on Tangles and its depiction of disability, she explores how Leavitt’s text tends towards using its graphic form to “[corroborate] the common verbal metaphor of “losing one’s identity” (82) due to Alzheimer’s. For instance, she highlights how as Midge’s condition worsens throughout the text, “the trope of losing one’s sense of personhood is visually depicted in the drawings of Midge’s eyes and expression” (81). Even though Leavitt’s illustrations value simplicity over lifelike accuracy, Midge’s expressions and temperament are clearly readable. Before Midge’s Alzheimer’s is diagnosed, she is lively and expressive. For instance, when the chapter “Sisters” explores the relationship between Midge and her sisters (13), Midge runs through a whole host of feelings that the reader can visibly discern. Her anguish at the loss of her parents is expressed through her downturned eyebrows and frown (Fig. 1), while a panel showing her kindergarten class displays a contented smile, with half-closed eyelids that communicate a calm appreciation for her students. The annoyed anger at her daughters is just as readable as her shock at their fighting (Fig. 2). Even though the illustrations are simplistic and quite small compared to the page as a whole, there is a subtlety to Midge’s expression that suggests complex personhood.

However, as Midge’s disease progresses, her “visual characterization is taken over by a sort of blank stare that dehumanizes her” by “[situating] her as an improper person, someone outside the domain of the subject” (81-82). For instance in the chapter “Y Tu Loquita”, Midge’s expressive countenance is replaced with the aforementioned blank stare; her mouth is a moderately downturned line, her eyes are completely hidden behind the lenses of her glasses, and her eyebrows are missing altogether (Fig. 3). The visual deletion of Midge’s affect suggests that the locus of her identity is breaking down - that her very personhood is beginning to vanish.

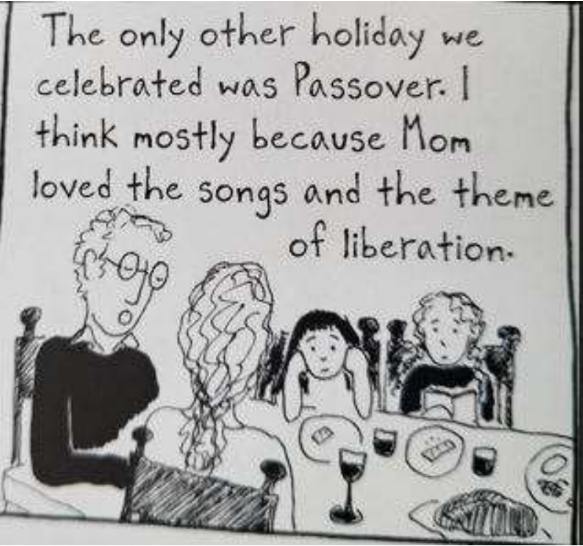

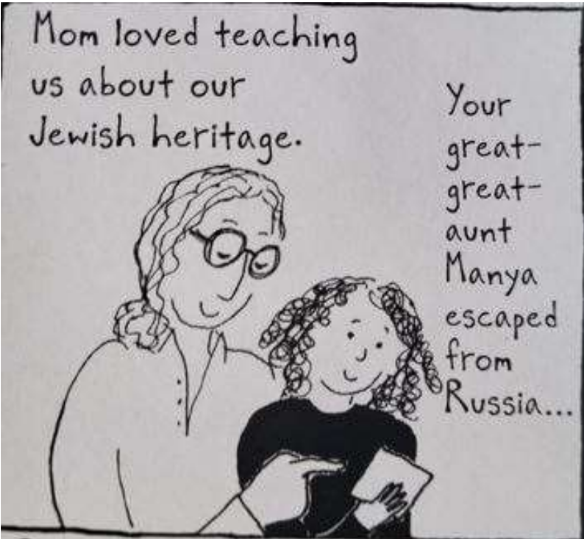

Another visual motif that expresses the breakdown of Midge’s personhood is the strength of the lines which form her figure on the page, particularly her tangled hair. Earlier in the text, Midge’s locks are well-defined when compared to the rest of her head. For instance, on a spread between pages 44 and 45, her hair comes down from her scalp and gathers in what appears to be a loose ponytail near the bottom of her neck. The image of her side profile (Fig. 4) showcases her carefully put-together hair, with firm roots and numerous strands (45). From the multiple angles of her head across these two pages – the panel at the dinner table (Fig. 5) shows a back view (44), while her teaching her daughters about Jewish heritage has a frontal view (Fig. 6) – her hair almost has a sense of three-dimensionality to it.

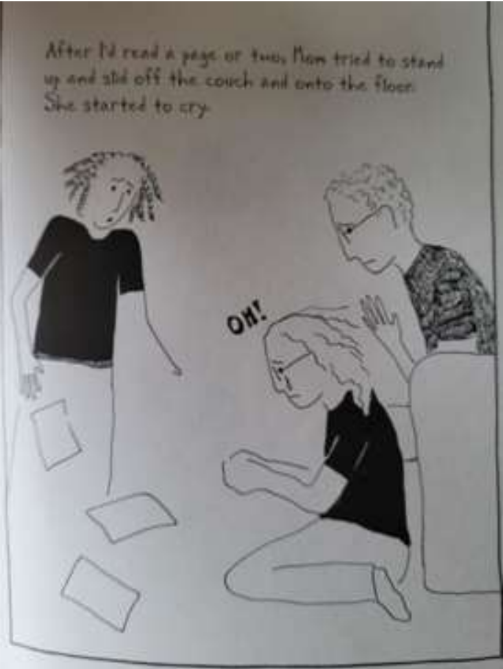

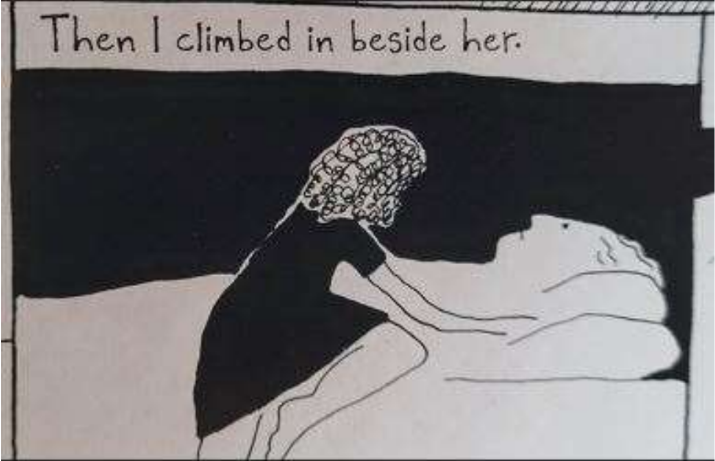

However, as Midge’s disease progresses, her hair degenerates alongside the rest of her character design. In the chapter “The Things I Don’t Know” (89), for example, her hair has become disordered and whispy. It is formed of far fewer strands, which almost seem to hover in place and create gaps that break up the profile of her head (Fig. 7). In fact, her entire body is disjointed and tenuously constructed; the lines that form her legs and arms are wobbly and disconnected, as if she is unravelling before our very eyes. The dissolution of Midge is even more overt in the chapter “Popping Up”, which recounts the difficulties of getting Midge to sleep. On one panel (Fig. 8), we see Midge in profile. However, instead of being drawn with any kind of spatial presence, her entire form is nothing more than a single, unbroken line separating pure black and pure white, with a dot for an eye and three strands of hair. Her body is quite literally a blank space, formed by the division between the inky black of the background and the textureless void of the unmarked page. The scant features of her face do little to add any vitality; her affectless stare conjures up a corpse’s visage. She is little more than a single thread stretched across blank, white space. The contrast between the vibrant, energetic Midge of the text’s beginning chapters and the totalizing lack of presence embodied by the Alzheimer's-stricken Midge casts the disease as death-in-life. By slowly deleting the signifiers of identity until nothing but a motionless husk remains, the text “[situates] persons with Alzheimer’s disease as being ‘non-persons,’ ‘already dead,’ ‘not human,’ and so forth” (DALMASO).

3. Relational Subjectivity

However, even though Tangles is so forward with its imagery of absent personhood, this is not the only reading that can be gleaned from the text. Leavitt’s text contains an alternate perspective which opposes the problematic implications of the depth model. In fact, several more contemporary philosophers and neuroscientists have proposed theories that oppose the mind/body divide, and instead suggest that the two are fundamentally interlinked.

According to Heersmink, there is “a wealth of empirical evidence in cognitive psychology” which suggests that “human memory is not like an archive” at all (3). Instead of memory and identity acting like a repository of information that “provide[s] a reliable and accurate link between two time slices of a person” (3), our sense of self may instead be an “integrative and holistic” process of relational narrativity. Heersmink asserts that rather than our identity simply being the sum total of our stored knowledge, personhood is a distributed construction – an amalgamation of disparate fragments that are stitched together to form a coherent whole. Our minds do not just store and recall knowledge, but instead suture together the totality of the “events, actions, objects, individuals, and thoughts, feelings, moods, and emotions” that surround us every day. Through a process that Peter Goldie calls “Emplotment”, we “[shape], [organize], and [colour] the raw material into a narrative structure” (3).

In this sense, the human mind is not “the splendidly self-enclosed, mastering center of secure identity and control it was once deemed to be” (PARLATI 57). Both the “‘storing place’ metaphor” which dominated the writings of Locke and Descartes and the individual monad that Jameson discusses are replaced with a “narrative act” – a site of “‘embodied personhood’” where the individual is “one element in the ongoing conversational processes that intersect and interpellate selves and environments” (57). This iterative, distributed self is similar to the Deleuzian “Residuum-subject”: instead of selfhood filtering in a linear direction from the outside world to the essence in the depths, the Residuum-subject floats “on the periphery, with not a fixed identity, forever decentered, defined by the states through which it passes” (DELEUZE and GUATTARI 20). In this model, identity is “not brain-bound”; it is contingent on what surrounds it, “extended and distributed across an embodied agent and environmental resources” (HEERSMINK 4).

It is important to note that this relational subjectivity is not passive, nor is this nexus of cultural, spatial, and personal meaning objective or pre-defined. Rather, the way we materially, psychically, and temporally situate ourselves relies on the self-directed act of interpretation. Everything from cultural conventions, to interpersonal relationships, and even the very words we use to express our views rely on the capacity to, in a sense, read the world around us like a text and make sense of the text’s conventions, associations, and affects. It is useful to think of the association between cultural or personal objects and their connotative meanings semiotically. In the original linguistic context of semiotics, the signifier and signified – or a word and its associated meaning – are arbitrarily positioned. As Ferdinand De Saussure astutely posits, “The idea of 'sister' is not linked by any inner relationship to the succession of sounds [...] which serves as its signifier" (828). There is nothing particularly ‘sister-like’ about the word ‘sister’ - the relationship between the word and the mental concept of a ‘sister’ is wholly arbitrary. The same is true of all linguistic signs.

A cultural sign, formed from the signifier of a particular cultural object and the signified of the object's social meaning, is just as arbitrary as a linguistic one. The clothes we wear, the food we eat, the places we live, and even more nebulous cultural constructs like gender, race, or class do not contain within them an objective meaning that is transmitted to us: as Sarah Ahmed puts it, “we do not love and hate because objects are good or bad” in and of themselves (5). Rather, an object’s signification involves an “attribution of significance” – a “reading [of] the contact we have” between ourselves and the encountered object in the present, along with the consideration of material contexts, social conventions, and “histories that come before the subject” (6). Dick Hibdge calls this process of cultural interpretation the decoding of “connotative codes”. These codes act as “‘maps of meaning’” which “cut across a range of potential meanings, making certain meanings available and ruling others out of court” (HIBDIGE 14); by following a map of meaning, we situate ourselves in concert with the rest of the world and turn away from meanings that would not make sense. To engage in the process of self-narrativity, we each must navigate the web of signification through a multitude of overlapping codes and conventions.

That our identity is assembled from a collection of raw materials and organized into a uniform structure is not only fundamental to our understanding of personal narratives, but to textual narratives of all forms. However, the process of narrative coherence does not rest solely on the suturing of visible fragments: it is equally as important to consider how we are to bridge the gaps between these fragments. In fact, Wolfgang Iser asserts that textual gaps and ellipses “function as a kind of pivot on which the whole text-reader relationship revolves”. This is because textual gaps “stimulate the process of ideation to be performed by the reader on terms set by the text” (1455). Iser goes so far as to say that the blanks of a text are more important than what we can see, and that “[w]hat is said only appears to take on significance to what is not said” (1454). The gaps demarcate the “unseen joints of the text” and signal undiscovered “schemata and textual perspectives” that require intentional “ideation on the reader’s part” to make sense of (1455-1456). The text essentially wields its gaps like a call to action - a demand to comb over “what is missing” and put in the effort to “[fill] the blanks with projections” (1454).

While Iser’s assertions about the importance of gap-filling apply to all kinds of texts, his theory is of particular importance to the medium of comics. Scott McCloud argues that sequential graphic narratives are so effective an artistic medium because they tap into the very same process of Emplotment that allows the embodied mind to construct itself. He explains that while “[a]ll of us perceive the world as a whole through the experience of our senses”, these same senses “can only reveal a world that is fragmented and incomplete” because “[e]ven the most widely travelled mind can only see so much of the world”. In this view, the world fundamentally lacks objective cohesion because our “perception of ‘reality’ is [...] based on mere fragments”. However, humanity is still capable of “observing the parts but perceiving the whole” through a process he calls “Closure” (61-63). In the same way that Goldie’s Emplotment allows us to generate a cohesive autobiographical narrative through the assembly of disparate parts, “closure allows us to connect [...] moments and mentally construct a continuous, unified reality” (67). In graphic narrative specifically, closure occurs in “the gutter”: the blank space between panels (66). Even though “[n]othing is seen between the two panels [...] experience tells you that something must be there” (67), so the brain uses closure to fill the void and lend cohesion to the “jagged, staccato rhythm of unconnected moments” (67).

It is through drawing closure that Tangles imbues Midge with a sense of distributed, embodied identity, even if so much of the text’s imagery connotes her identity as being “concentrated in her head” (82). Through the text’s frequent use of fragmentary imagery – with parts of Midge’s body or her experience with her surroundings being split off or fractured from a unified whole – Tangles wields what Jameson calls a ‘schizophrenic aesthetic’ to embody her impaired capacity to engage in narrative closure. A schizophrenic aesthetic is not the literal representation of the psychiatric condition schizophrenia, of course; rather, it is an aesthetic turn in which the chain between signifier and signified “snaps” and produces “schizophrenia in the form of a rubble of distinct and unrelated signifiers” (34). The schizophrenic aesthetic lacks coherence – it is “reduced to an experience of pure material signifiers, or, in other words, a series of pure and unrelated presents in time” (34). By representing Midge’s experience of the world as one of disconnection instead of deletion, the text constructs the Alzheimer’s-stricken identity as one that is not so much absent as it is impaired. Midge has not been erased; rather, she has been prevented from making meaningful connections between aspects of her world.

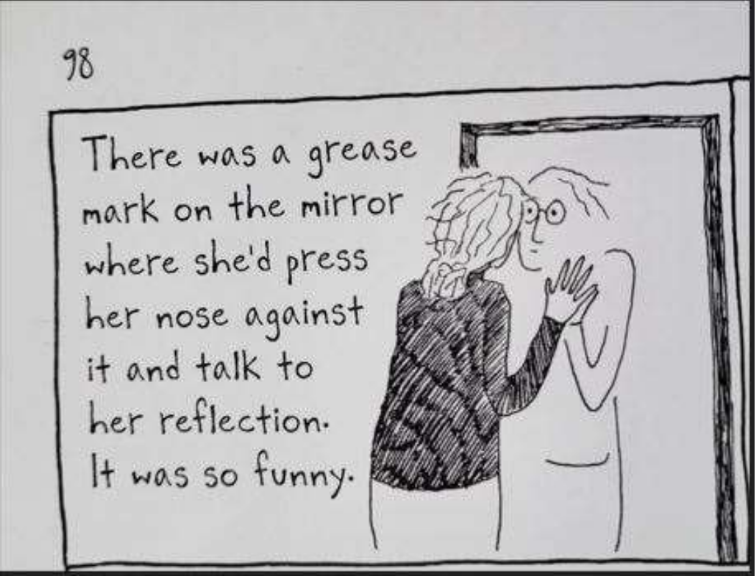

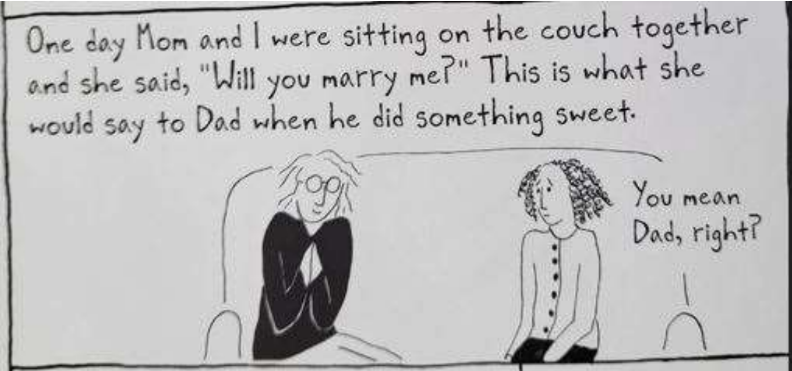

There are several scenes in the text which suggest that Alzheimer’s has fragmented Midge’s capacity to engage in the act of closure, rather than dissolve her singular identity. During the chapter “Why Are You Depressed” (97-98), for instance, Leavitt visualizes Midge’s fragmented grasp on the physical world in several single-panel anecdotes. In one panel (Fig. 9), Midge “[presses] her nose against [a mirror] and [talks] to her reflection” (98); her expression is one of meek curiosity, which suggests the inability to connect the image of herself with herself. Instead, she believes it is another person, and converses with it. She has lost the capacity to connect the abstraction of a reflected image with her own person. In another panel (Fig. 10), Midge says “will you marry me” to Leavitt, who explains that this phrase is ordinarily said “to [her] Dad when he did something sweet”. Midge displays fragments of her “old” identity in that she recalls this specific phrase being associated with loved ones, but her inability to distinguish between people causes her to say the phrase to the wrong person. The raw material of recollection is still present in Midge’s mind to some degree, but the disease has fragmented their cohesion and left a jumble of loose expressions and images.

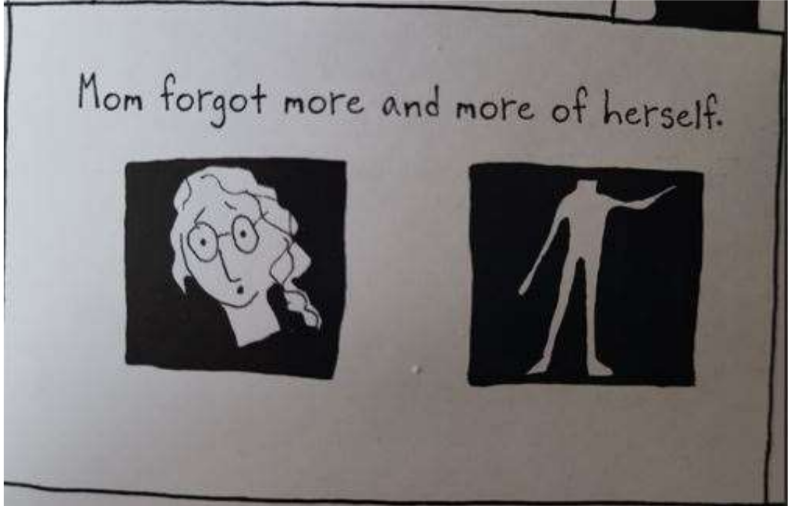

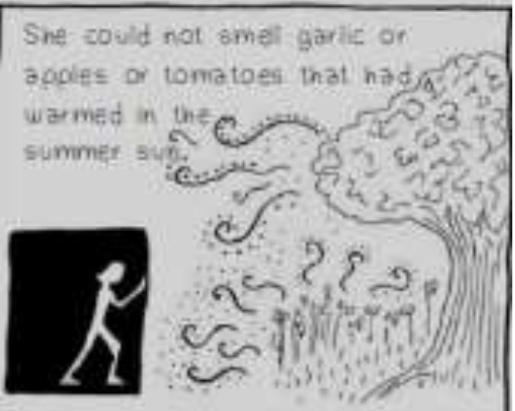

In another chapter, “Taste and Smell” (59-60), Leavitt uses a striking visual metaphor to express Midge’s inability to draw closure between her mind, her body, and the world around her. During a series of panels in which Leavitt explains Midge’s loss of smell, Midge’s head and body are drawn into separate, pitch-black boxes (Fig. 11), with the accompanying text “Mom lost more and more of herself” (59). This disconnection between her mind and her body functions in two ways. While it points towards the physical loss of smell, it also expresses the loss of a second connection: the inability to properly interface with every aspect of the delicious-smelling foods she loves so much, along with the personal histories that these smells and tastes connote (Fig. 12). Because she cannot “smell garlic or apples or tomatoes that had warmed in the summer sun” (59), she is not just missing out on the taste of food itself, but the connections that spread out from the food. Midge’s separation from her body impacts her sense of self and “[frightens] her”; the deadening of her smell means that she can no longer use the information from an entire sense to build closure. Her selfhood is being spread thin and cut off from itself until it can no longer cohere.

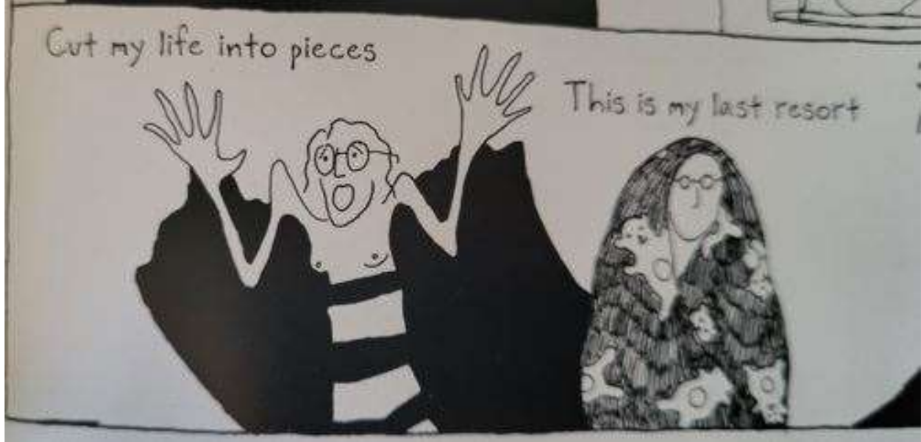

A similar visual metaphor is used in the chapter “Cut My Life Into Pieces”, which continues the motif of being cut apart to suggest an inability to suture together a cohesive self. Leavitt explains that in the year 2001, she heard a “song on the radio called Last Resort by Papa Roach”, which became a “soundtrack to [Midge’s] struggling”. Along the bottom of the page, we are presented with a striking scene; beneath the lyric “cut my life into pieces” is the image of a naked, screaming Midge, whose midsection has been chopped into slices by thick lines of black ink (Fig. 13). Similarly to how “Taste and Smell” used blocks of ink to fracture Midge, this chapter literally disassembles her into rubble and fragments. However, the metaphor of the fragmented self poignantly asserts Midge’s right to selfhood because despite her being sliced apart, the pieces are all still there. Alzheimer’s did not scour Midge from her own brain and leave an empty husk behind; rather, Alzheimer’s disassembled her and left the pieces scattered about in her head. It is inaccurate to say that Midge does not exist anymore; rather, the means by which she uses the raw materials of the world around her to create a cohesive, unified self has been impaired.

4. Conclusion

I believe the heart of the conversation surrounding Midge’s identity in Tangles comes down to this question: is she still there? Can it be said that she is still in her head somewhere, or has she been destroyed? The answer to this question depends on how identity and selfhood is formulated, and the framing one uses can severely impact how sufferers are seen by the able-minded. If identity is conceptualized as being the result of a functioning mind, or as the consequence of an efficient memory archive, then Alzheimer’s imparts a death-in-life; as Midge’s comprehension slips away, so too does her status as a human being. However, if identity is seen as broader – as being the sum total of our minds, our bodies, and the relationships we have with other people and the physical world – then the framing of Alzheimer’s as a disease shifts. Alzheimer’s is no longer the deletion of the self. Instead of Alzheimer’s causing an absence of identity, it instead causes an impairment of identity. This is an important distinction; the latter reading insists that Midge is, in one way or another, still a person who deserves to be loved and taken care of, instead of a once-inhabited shell of crumbling flesh. Alzheimer’s may have fragmented Midge’s identity, but the remaining pieces still deserve to be seen as human.

Appendix

Bibliographie

AHMED, Sara. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh University Press, 2014.

DALMASO, Renata Lucena. “The Visual Metaphor of Disability in Sarah Leavitt’s Graphic Memoir Tangles: A Story about Alzheimer’s, My Mother, and Me.” Ilha Do Desterro A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, vol. 68, no. 2, 2, Jan 2015, pp. 75–92.

DELEUZE, Gilles and Felix GUATTARI. “The Desiring-Machines.” Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Translated by Robert Hurley, Mark Seem and Helen R. Lane, University of Minnesota Press, 1983, pp. 1-50.

DE SAUSSURE, Ferdinand. “Course in General Linguistics.” The Norton Anthology of Theory of Criticism, 3rd Edition, Edited by William E. Cain et al., Norton & Company, 2018, pp. 824-840.

EL REFAIE, Elisabeth. Autobiographical Comics: Life Writing in Pictures. University Press of Mississippi, 2012.

GABORA, Liane M. “Conceptual Closure: How Memories Are Woven into an Interconnected Worldview.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 901, no. 1, Jan. 2006, pp. 42–53.

HEERSMINK, Richard. “Preserving Narrative Identity for Dementia Patients: Embodiment, Active Environments, and Distributed Memory.” Neuroethics, vol. 15, no. 1, Apr 2022, pp. 1-16.

HIBDIGE, Dick. “From Culture to Hegemony.” Subculture: the meaning of style, Routledge, 1979, pp. 5-19.

ISER, Wolfgang. “Interaction between Text and Reader.” The Norton Anthology of Theory of Criticism, 3rd Edition, Edited by William E. Cain et al., Norton & Company, 2018, pp. 1452-1460.

JAMESON, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Duke University Press, 1991.

LEAVITT, Sarah. Tangles: A Story about Alzheimer’s, My Mother, and Me. Skyhorse Publishing, 2012.

MCCLOUD, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. HarperCollins Publishers, 1993.

PARLATI, Marilena. “Mixing Memory: Discovering and Narrating the Other Selves of Alzheimer’s.” Prose Studies, vol. 42, no. 1, 2021, pp. 53–67.

“What is Alzheimer’s Disease?” Alzheimer’s Association, https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers.